Chapter OneLeaving Terminal Island

Chiyoko , 15

December 7, 1941 | Los Angeles, CA

From her perch in the fig tree, Chiyoko could see through the open French windows into the living room, where her parents were in the middle of a heated conversation. On Sunday afternoons like these, Chiyoko would often climb up the backyard tree to snack on fresh figs and listen to the sounds of the waves crashing onto the beach a few blocks away.

But today she had no appetite. Her parents had received a disturbing call about her grandma, who they had just seen that morning. Grandma had taken the ferry from San Pedro, the city in Los Angeles where she lived, to attend church on Terminal Island , the fishing community where Chiyoko and her family lived. Grandma made this trek every Sunday to attend church with the family.

Chiyoko’s uncle had called to share that earlier that morning, Japanese planes attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, killing more than 2,300 Americans. This afternoon, when he had gone to pick up Grandma from the ferry dock in San Pedro, armed guards swarmed the area. Grandma and several other Japanese Americans returning from Terminal Island were held and questioned for hours by the local police.

The attack at Pearl Harbor became the catalyzing force for the United States to declare war with Japan and officially enter into World War II . What happened to Chiyoko’s grandma confirmed that Terminal Island — a predominantly Japanese American community situated on the West Coast’s most important harbor — was already under heavy scrutiny and investigation.

The next two months passed in a nightmarish blur for Chiyoko’s family and all of the other Japanese Americans living on Terminal Island. Due to rising war hysteria , the FBI increased its surveillance of the Japanese American community. Armed soldiers in jeeps became a natural part of the landscape. Local businesses and homes were violently raided by FBI officials looking for any evidence of locals colluding with Japan — there was none. The FBI also rounded up all male cultural and civic leaders in the community. With no martial arts teachers left, the once bustling Fisherman’s Hall became vacant.

Then, in early February, all Japanese American men with commercial fishing lines — more than a third of the island’s total population — were arrested and eventually detained in Department of Justice camps .

Because Chiyoko’s dad was a shipbuilder and not a fisherman, he wasn’t targeted by the FBI — although he kept his suitcases packed just in case. Chiyoko’s house was also never subject to the frequent raids. The majority of Japanese Americans on Terminal Island lived in company-owned rental homes near the fish canneries. Chiyoko’s dad had bought and rehabbed a Victorian home on the other side of the island, which was formerly a Bohemian artists’ colony and resort town.

Why do you think the Japanese American community on Terminal Island was targeted for early forced removal?

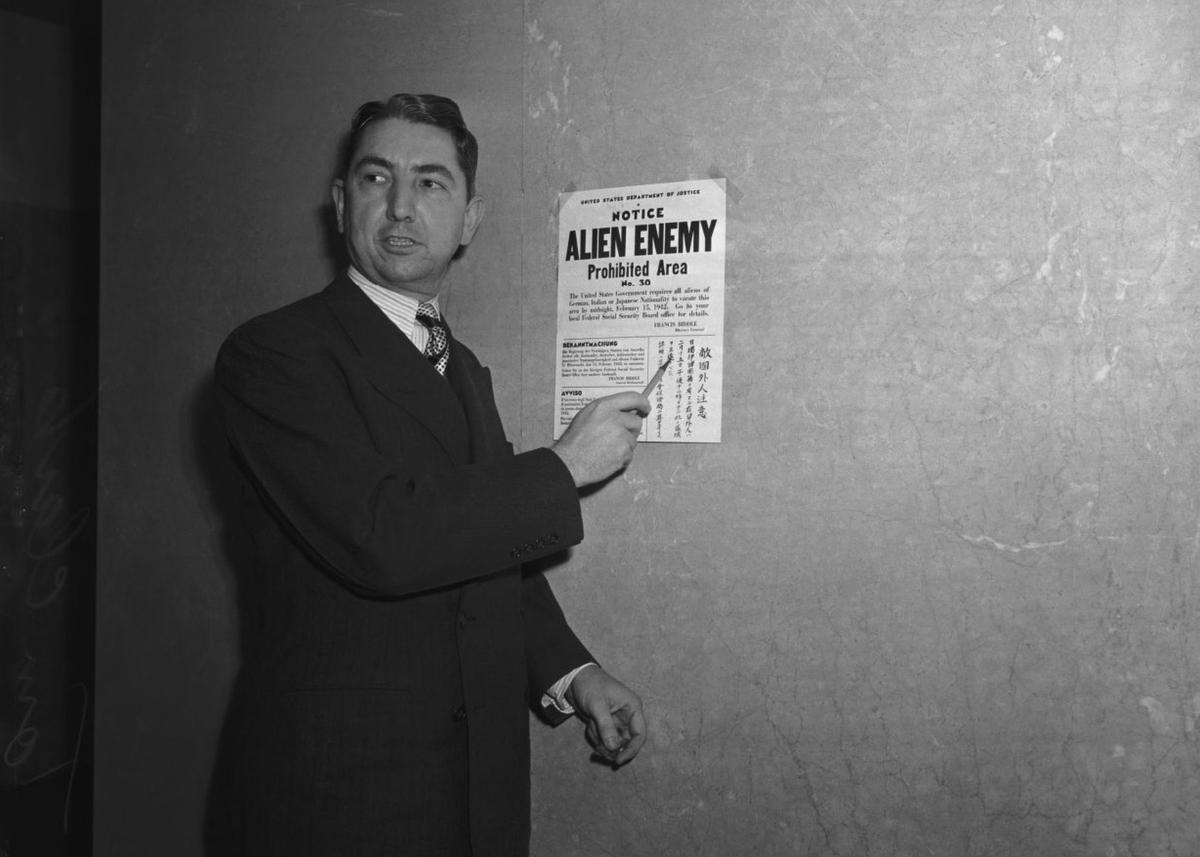

But the family wasn’t spared for long. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 , which divided the West Coast into military exclusion zones and set into motion the forced removal and imprisonment of around 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in those zones.

Less than a week later, armed soldiers informed Chiyoko’s parents that they had 48 hours to evacuate the island. There was no guidance for where they should go.

Chiyoko watched as her parents frantically tried to sell the gadgets and home appliances they had saved up for over the years. Some of them were brand new, like the refrigerator that dispensed ice cubes and the radio so powerful it could pick up music all the way in Japan.

Then there were the family heirlooms: the intricate Japanese porcelain dishes, called Imari, that Chiyoko’s mom used on special occasions like New Year’s, the little red surfboard her dad had made for her in his carpentry workshop, and the wooden pianola, or self-playing piano, that she and her two younger siblings would gleefully pump with their feet to generate music.

But selling a life’s worth of belongings in 48 hours was impossible. In the end, Chiyoko’s family left almost everything behind.

Ask Chiyoko...

Chapter TwoReporting behind barbed wire

Chiyoko , 16

1942 | Poston, Arizona

As the train creaked to a halt, Chiyoko peered underneath the window curtains that the guards had ordered them to shut for the duration of the ride. It was twilight, and in the distance she could see the silhouettes of mountains backdropped by a pale purple sky. Then, as the doors opened for disembarkment, Chiyoko felt a wave of dry heat permeate the already stuffy cabin.

It turned out the rumors were true — they had been sent to the desert.

Chiyoko watched armed soldiers stand guard as her dad helped the other women and kids in their train car retrieve their suitcases. He’d assumed a father figure role for everyone ever since the FBI roundups in February took away most of the men in the community.

Chiyoko was grateful her family had stayed safe and intact despite everything that happened since the fateful day when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Despite the rampant racism and xenophobia towards Japanese Americans, some people had looked out for them. After hearing about Terminal Island’s 48-hour evacuation order, leaders of the local Baptist church sent buses to take Chiyoko’s family and other Japanese American members to a sister church in Los Angeles.

For the next three months, that church housed Chiyoko’s immediate family plus her grandma, Uncle Yas, and Auntie Kiki, who were forced to evacuate their home in San Pedro. Church leaders tried their best to support the family through the upheaval, and even helped Chiyoko enroll at a nearby high school. But she missed her teachers and friends at her old high school. Plus, it was hard to feel engaged in classes when there was so much uncertainty about how long she would even be there.

Chiyoko knew they wouldn’t be allowed to stay in Los Angeles forever. In April, her parents heard talk of a new government agency called the War Relocation Authority that was building what they were calling Japanese American “relocation centers” in remote locations across the country.

Chiyoko wasn’t fooled by the term — these were concentration camps designed to confine civilians for military and political purposes. Japanese Americans were never charged with any crimes nor given the right to a fair trial. They were imprisoned solely because of their Japanese ancestry.

Chiyoko and her family were incarcerated at Poston concentration camp in Arizona, which was built on the Colorado River Indian Reservation near the state’s border with California. It didn’t take long after arriving for Chiyoko’s family to realize that their wooden barrack was not built to withstand the desert climate. The structures were made with green lumber, Chiyoko’s dad explained, which is why they shrunk in the heat and left gaps in the walls.

Upon arriving at Poston, Chiyoko’s dad threw himself into improving conditions for the family. To protect everyone during dust storms, he dug a large hole underneath their one-room barrack and covered it with wood planks. He built benches and lined them along the edges of the hole. From the safety of the “basement,” the family would sit and read as they waited out the storms.

Chiyoko’s dad used his carpentry skills to help others, too. After noticing that the camp latrines had no doors or partitions between the toilets, he installed wooden dividers to give people more privacy.

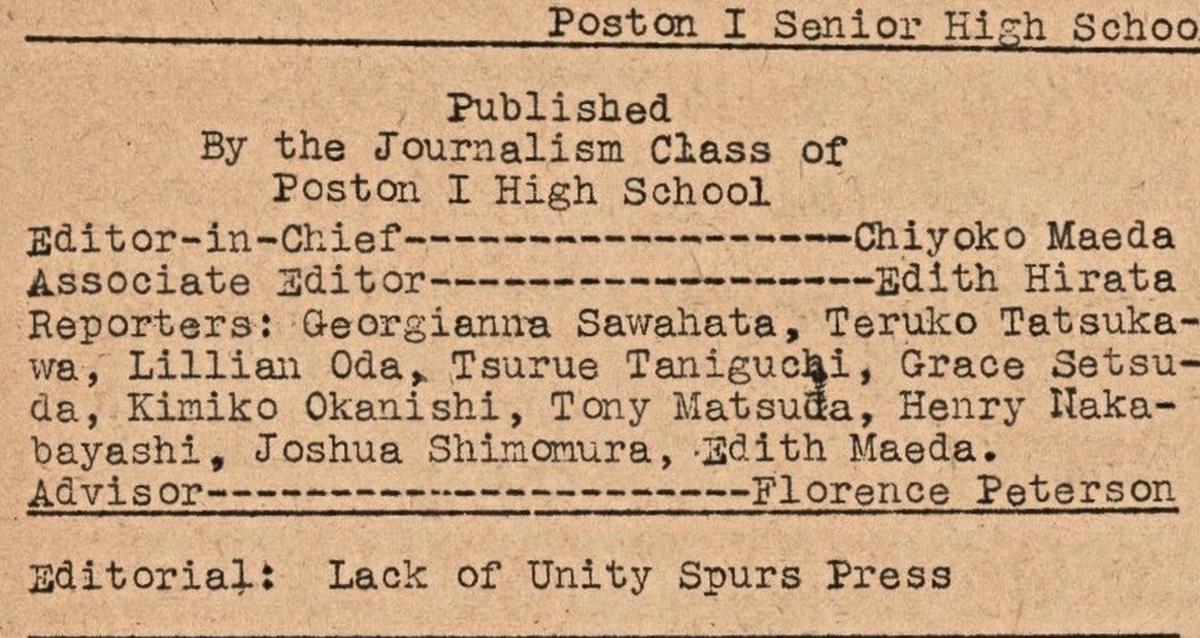

While her dad was busy improving the conditions at Poston, Chiyoko immersed herself in student life. She successfully ran for junior class historian and helped start a student newspaper called the “Kampus Krier" to report on the teen experience at Poston and create a sense of student unity.

But despite Chiyoko's efforts to make the most of her time at Poston, her dad was unhappy with the quality of the camp schools. He valued his kids getting a good education, and seeing Chiyoko’s high school years interrupted upset him more than any of the other injustices of camp life.

Chiyoko’s dad eventually learned of a student leave clearance program that allowed students to leave camp early to continue their education in the Midwest or east coast. He came up with a plan: Chiyoko would finish high school in Pennsylvania and live with her Auntie Kiki and Uncle Yas. Uncle Yas had fled Los Angeles for the East Coast to avoid being incarcerated, and had found work in a poultry factory in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Why do you think Chiyoko’s parents wanted her to leave camp early?

In October of 1943, almost a year and a half after she arrived in Poston, Chiyoko’s application for early leave was approved.

On the bus ride away from camp, Chiyoko watched as the rows of dusty barracks grew smaller and smaller. She imagined her family sitting together in the hole beneath their room, not knowing whether it would be months or years before it would be their turn to leave.

It would be several years before she saw any of them again.

Ask Chiyoko...

Chapter ThreeTaking control of the narrative

Chiyoko , 18

1944 | Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Chiyoko shielded her eyes and squinted at the crowd of faces in front of her. It was a warm afternoon in late July, and she was standing next to her Auntie Kiki in Williamson Park, a 54-acre grassy expanse overlooking the city of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. They were the featured speakers at the Lancaster Inter-racial Council annual picnic event.

Since arriving in Lancaster nine months ago, Chiyoko had spoken publicly many times about her experience at Poston. She’d presented to several groups at the local Lutheran Church and once to a business club at the Y.W.C.A. People were curious to learn how a Japanese American teenager ended up in Pennsylvania — and almost nobody had heard about the incarceration camps.

At Williamson Park, Chiyoko talked about being forced to leave the Victorian home with the French windows on Terminal Island, and what life was like in camp. She detailed the multi-day train ride from Parker, Arizona to Chicago, Illinois, where she’d stayed at a Baptist seminary on the city’s west side while waiting for Uncle Yas to retrieve her. She told the group about how her family was still behind barbed wire.

Auntie Kiki talked about how the community in Lancaster had warmly welcomed her, Chiyoko, and Uncle Yas, and how a couple named Frank and Edith Weaver agreed to rent two bedrooms in their home to them.

Chiyoko agreed with Auntie Kiki. Lancaster was a pleasant place to finish high school, even though she was treated as somewhat of a curiosity. At East Lampeter High, her classmates became lifelong friends. She taught them folk dancing, how to use a typewriter and — like she had done in Poston — helped start a school newspaper. In a letter published in Poston’s “Kampus Krier," Chiyoko wrote to her friends who were still in camp about her experiences as a Japanese American in Lancaster.

The next fall, Chiyoko started freshman year at Houghton College, a private liberal arts school in western New York. Of the several thousand Japanese American students who were granted leave clearance, most attended small schools like Houghton in the Midwest and East Coast because larger universities were not allowed to, or refused, to admit Japanese Americans .

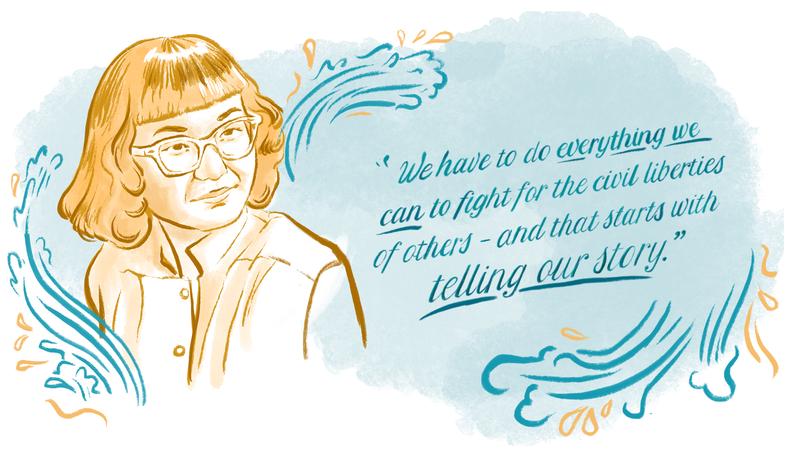

While at Houghton, Chiyoko’s interest in journalism grew, and she wrote regularly for the school newspaper. During these years, she also continued to speak publicly about her incarceration experience.

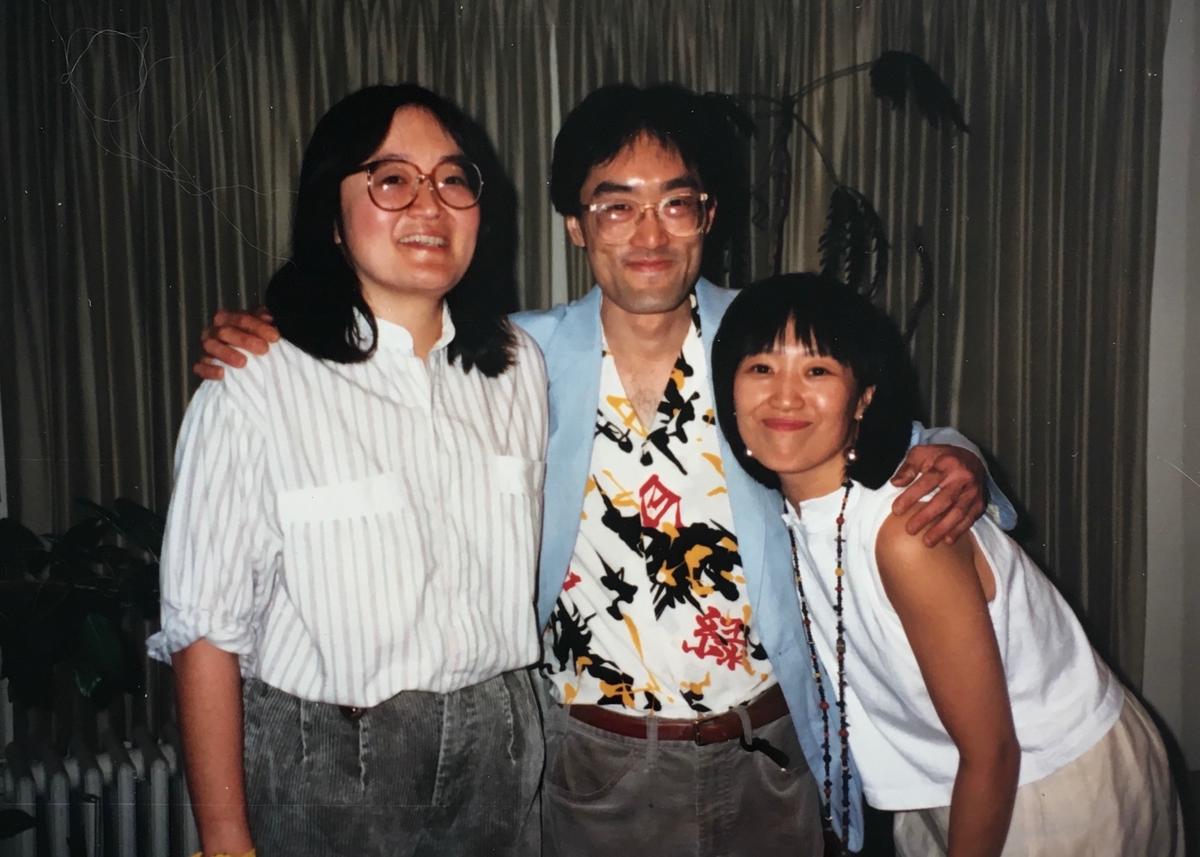

After graduating in 1948, Chiyoko finally reunited with her family in Chicago.

In late 1945, Chiyoko’s parents and siblings left Poston for Chicago as part of a WRA resettlement program to redistribute Japanese Americans across the Midwest and East Coast. The WRA didn’t want Japanese Americans to return to west coast communities like the one Chiyoko grew up in on Terminal Island — they wanted them to spread out and assimilate into white, middle class society.

The WRA chose Chicago as one of the main destinations for resettlement because the city needed workers to fill the void created by the war effort, and because Chicagoans were seen as more tolerant towards Japanese Americans. Unlike the West Coast, Chicago only had a few hundred Japanese Americans living in the city before the war.

After Chiyoko arrived in Chicago, she took a job at the Chicago Resettlers Committee , a social service organization formed to help Japanese Americans coming from the camps find jobs and housing in the city.

As Chiyoko helped other Japanese Americans settle into their new lives in Chicago, she noticed that most people hardly ever talked about their experiences in the camps. When it did come up, most simply responded with the Japanese phrase “Shikata ga nai," which translates to: “It cannot be helped."

Chiyoko couldn’t feel more differently. She wanted to educate others about what happened to Japanese Americans so history wouldn’t repeat itself.

She knew she had to find a way to keep telling her story.

Eventually, Chiyoko found a way to apply her passion for writing and education at Scott Foresman, a school textbook publisher in Glenview, Illinois. There, she developed English and history curricula that were taught in classrooms across the country.

Chiyoko would travel the country searching for work to feature from a diverse range of authors. It was important to her that all students saw people like themselves reflected in the curriculum. Sometimes, when Chiyoko had to come up with fictitious characters for stories in English textbooks, she would give them Japanese last names like “Tanaka" or “Suzuki."

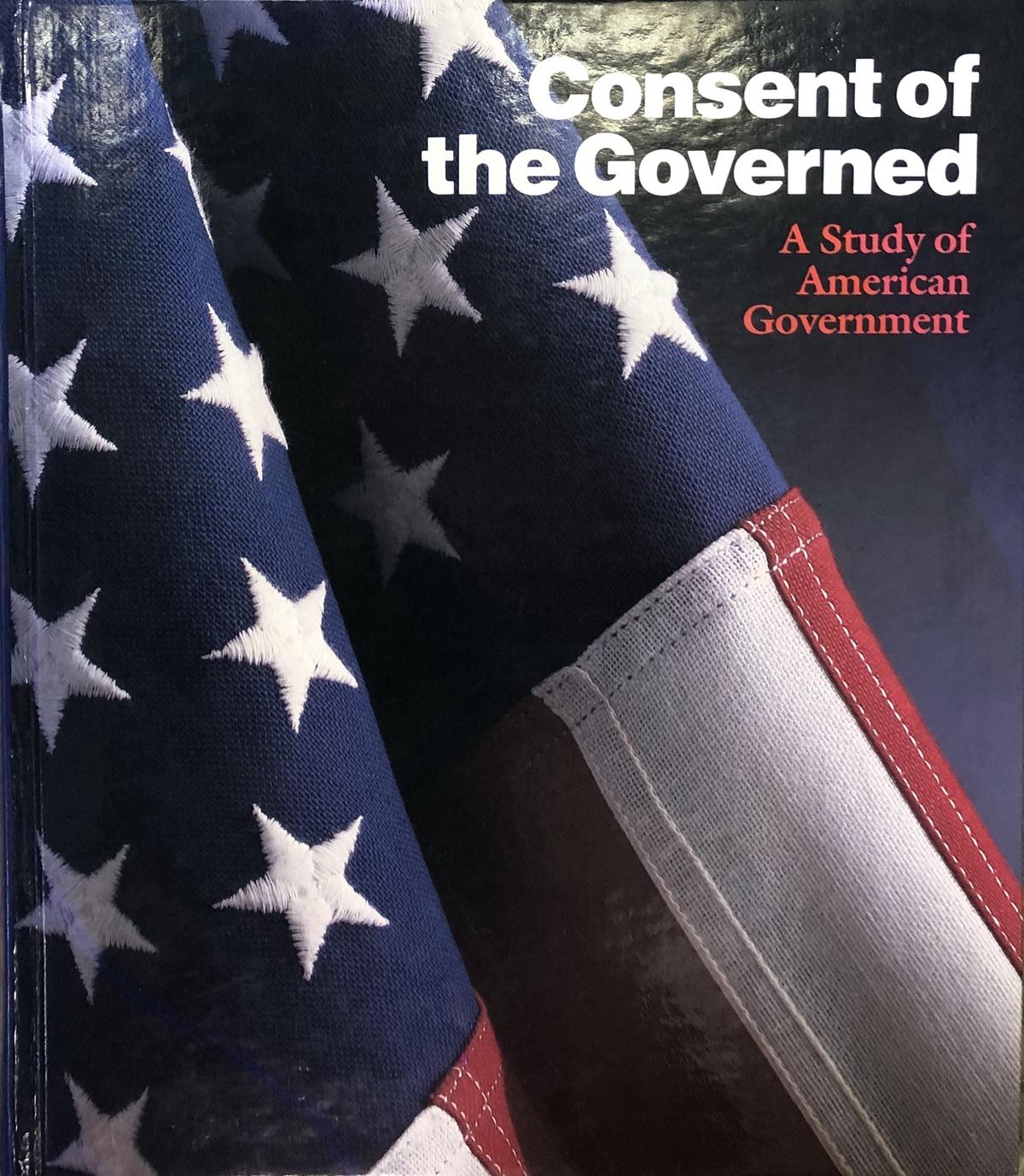

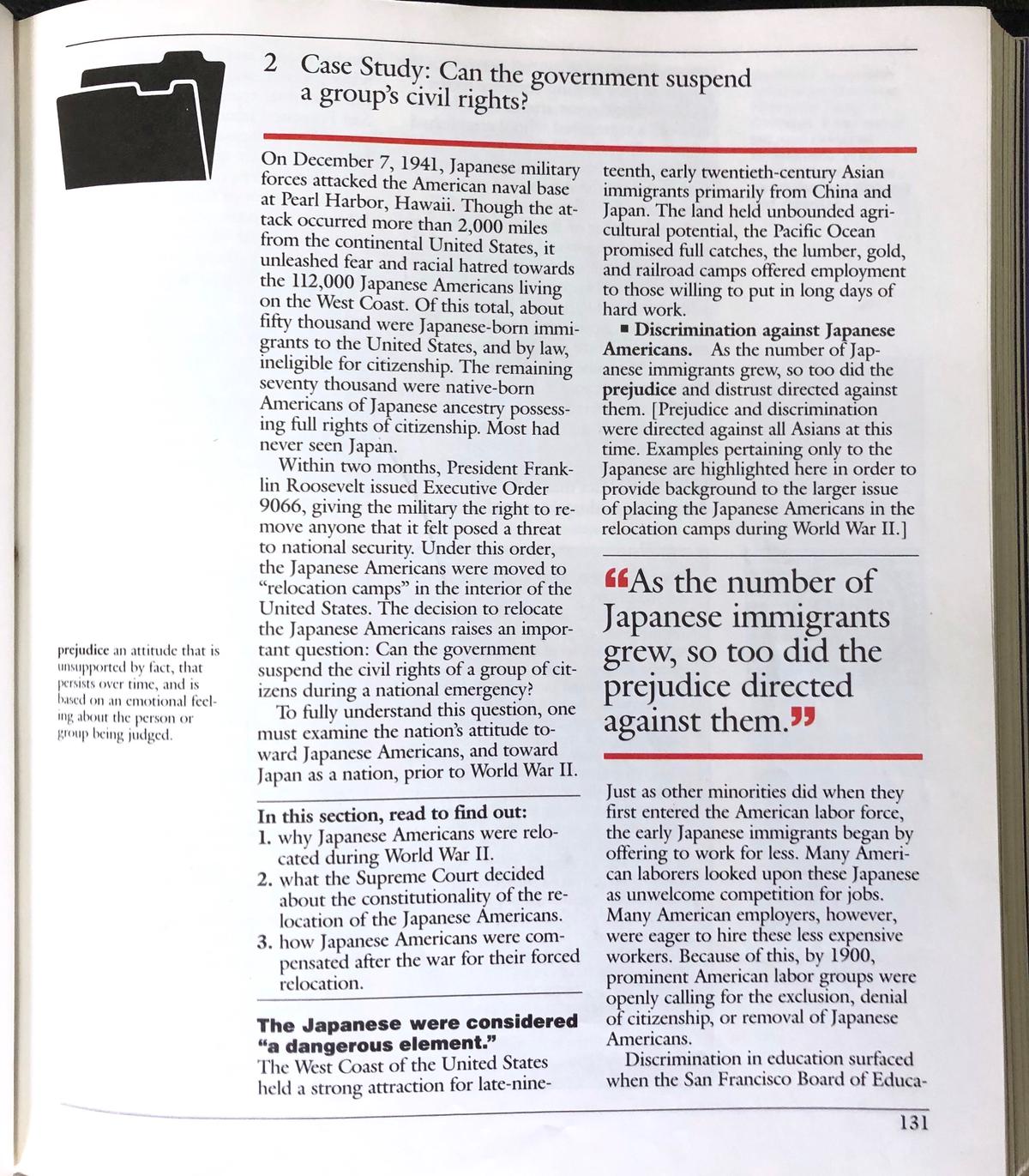

Chiyoko’s most meaningful project at Scott Foresman was helping edit a chapter about Japanese American incarceration. It was for a history book called “Consent of the Governed." The chapter posed the question: Can the government suspend the civil rights of a group of citizens during a national emergency?

In the first draft of the chapter, Chiyoko noticed something off: the writer seemed to suggest that what the government did to Japanese Americans was justified. It wasn’t explicitly stated, but the tone of the writing implied it. It had to do with word choice and framing.

For Chiyoko, how history was portrayed to students had huge implications for the lessons they would take away from it. Words were a form of power — in one breath, they could rationalize the imprisonment of an entire community. In another, they could make an argument that Japanese American incarceration was morally and legally wrong.

Chiyoko worked tirelessly with the writer and other editors to revise the draft until it conveyed the right lesson.

Ask Chiyoko...

Chapter FourA lesson in civil liberties

Teresa , 20

1974 | Washington, D.C.

Teresa ascended the white marble steps of the U.S. Supreme Court building and gazed up past the Corinthian columns. Engraved in stone on the facade was the phrase: Equal justice under law.

Teresa was in her junior year of college, and the visit to the Supreme Court was part of a class she was taking about constitutional law. Ever since she was a kid, Teresa understood the importance of constitutional rights . Her mom Chiyoko would tell her how these rights were denied for Japanese Americans like herself during World War II.

Once they were inside the Supreme Court, Teresa’s class met with Tom C. Clark , a retired Associate Justice. Teresa was caught off guard by Justice Clark’s opening question.

“Is there anyone here of Japanese ancestry?" he asked.

Teresa raised her hand. Justice Clark explained to the class that he was part of the U.S. Department of Justice when World War II broke out. He was appointed chief of the West Coast offices and worked directly with military officials to plan and execute the incarceration of Japanese Americans. He told Teresa it was the biggest mistake of his career and to extend his apology to everyone in her family.

Teresa was moved by Justice Clark’s words. She knew the apology would mean a lot to her mom, who had spoken out against Japanese American incarceration since she was a teenager.

Why do you think it was meaningful for Teresa to hear the apology from Justice Clark?

Growing up, Teresa didn’t experience the same overt racial discrimination that her parents had during World War II. But it still played out — just in more subtle ways.

When Teresa and her younger brother were toddlers, her parents wanted to move from the Andersonville neighborhood on Chicago’s North Side to a suburb with a top rated high school. Many other Japanese American families followed a similar pattern of moving from the city to the suburbs for educational opportunities.

But when Teresa’s parents inquired about homes in the predominantly white suburbs of Evanston and Park Ridge, real estate agents kept telling them, “We don’t think you’d be happy here.” They got the hint.

Finally, some white friends who worked at Northwestern University offered to rent the family a home they owned in Wilmette, a suburb north of Chicago. When the Omachis moved in, several families on their block were upset about the new Asian neighbors. The friends who worked at Northwestern placated the other families by vouching for Teresa’s family’s “Americanness.” Many other Japanese American families faced similar discrimination when moving to the suburbs.

In Wilmette, Teresa was one of the only Asian students in her class. Other kids would taunt her about her race — once, she told her parents she wouldn’t go back to school until she had blonde hair and blue eyes.

For Chiyoko, writing was her tool to fight discrimination and achieve justice. For Teresa, it was the law. After taking the constitutional law class in college, Teresa graduated and worked as a paralegal in Chicago for a couple of years before attending law school at UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, CA.

While she was a student, Teresa helped with the defense of Black Panther Geronimo Pratt , who was framed for murder by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Pratt was eventually released after spending more than 20 years in prison and received a civil settlement.

After graduating from law school, Teresa spent nine years in California focused on workers’ compensation law. She represented employees who contracted illnesses caused by exposure to asbestos, a toxic material that can cause a range of lung problems.

In 1988, while Teresa was working in California, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act as a way to atone and apologize for the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

How was the apology different when it came from the U.S. government?

The act, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, allowed the government to issue $20,000 in reparations to all living former incarcerees, along with an apology that recognized a fundamental violation of the basic civil liberties and constitutional rights of Japanese Americans. It described incarceration as the result of “race hysteria, war prejudice, and the failure of political leadership" at the time.

To Teresa, the monetary sum paled in comparison to the power of the apology. And this time, it wasn’t coming from a remorseful individual like Justice Clark, but from the United States government.

Ask Teresa...

Chapter FiveA story with lasting lessons

Chris , 11

2001 | Deerfield, Illinois

Chris took a seat in the auditorium next to his 6th grade classmates. On stage, his grandma Chiyoko — also known as “Gran" — stood at a podium, barely tall enough to reach the mic.

Today, Gran was speaking to Chris’s grade about her incarceration experience during World War II. Chris grew up hearing her stories often, but this was the first time many of his classmates were hearing directly from a camp survivor.

Despite Gran’s tiny stature, she filled the room. Chris’s classmates were captivated by her memories of growing up on Terminal Island. They shifted in discomfort when she talked about Executive Order 9066 and the poor living conditions at Poston. They laughed at her story about moving to Lancaster, Pennsylvania and trying to convince her high school principal that she was “yellow.”

After the assembly, Chris’s classmates crowded around Gran to thank her for sharing her experiences. They thanked Chris, too, and told him how moved they were by his family’s story. Chris beamed with pride.

Gran was retired by the time Chris was born, so the two of them spent lots of time together during his childhood. Gran taught Chris to appreciate art and culture from all over the world. They would see seasonal shows at the Lyric Opera and Chicago Symphony Orchestra. On weekend afternoons, they would wander the galleries of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Through Gran, Chris also met people of all ages and backgrounds. Gran had a way of charming everyone she met — from post office clerks to grocery store baggers. He admired how she could connect with just about anyone. Gran was an active member of Ravenswood Fellowship United Methodist Church and would often take Chris to dinners and parties with her many church friends.

During Chris’s junior year of high school, he and Gran became even closer. His mom Teresa got a job as Assistant Attorney General for the state of Illinois. The job required her to move to the capital, Springfield, and Chris didn’t want to move in the middle of high school. So he decided to live with Gran.

During the two years they lived together, Chris and Gran became each other’s best friend. They’d treat themselves to dinner at their favorite Japanese restaurant, Renga-Tei. They supported each other through big life changes. Chris’s grandpa Akira had recently passed away, and Gran was grieving and adjusting to life without her husband. Meanwhile, Chris was learning to accept his sexuality and racial identity.

Chris’s dad is Mexican American and his mom is Japanese American. Growing up, people would constantly question his racial background because of the way he looked. They’d ask, “Where are you from?" or “What are you?"

Sometimes the questions came from a place of genuine curiosity, but that didn’t prevent Chris from feeling othered because of his racial identity. He knew it would be easy to become bitter and resentful whenever anyone asked a question about his background. But then he thought about Gran, who, when faced with extraordinary racial discrimination, had committed her life to educating others.

Now, whenever people ask Chris where his family is from, he uses it as an opportunity to talk about how his Japanese American grandparents were incarcerated during World War II. He also uses Instagram as a platform to share his favorite memories with Gran and talk about her story.

In the spring of 2021, Chris felt compelled to do something more. Hate crimes towards Asian Americans had skyrocketed during the pandemic, and on March 16, eight people, including six Asian women, were shot to death at Atlanta spas.

Chris decided to use the fundraising feature on Instagram to raise money for Asian Americans Advancing Justice, an organization that uses education, litigation, and public policy advocacy to advance civil and human rights for Asian Americans and build an equitable society for all.

How is Chris keeping Chiyoko's story alive and relevant in today's context?

To promote the fundraiser, Chris posted a slideshow of photos, including one of his grandparents on their wedding day, and a timeline of anti-Asian laws and actions over the course of U.S. history.

Chris believes that history dies unless you retell it and put it into context for new people. In his post, he expressed his commitment to sharing his family’s story:

“I’ve spoken a lot about my family on Instagram before so I will keep this brief – I could go on forever and am happy to with anyone who is interested. Both of my grandparents (American citizens, both born in California in the 1920s) were incarcerated with their families in Japanese internment camps of WWII. This civic violation is the backbone of my family’s history. It inspired my mother to become an attorney, and has been the lens through which she, my uncle, and myself see this country and entire world. So today’s violence does not come as a surprise. Racist and violent rhetoric for centuries has contributed to today’s atmosphere. But we are all capable of change, growth, learning, and understanding. It can only happen through deliberate education, compassion, and policy change."

A week into the month-long fundraiser, Chris exceeded his original goal by 800%.