Chapter OneWhere’s Dad?

Kaz , 2

1941 | San Francisco, CA

Kaz can barely remember what San Francisco’s Japantown was like before it became a military zone.

He was just a toddler when his once-bustling Japanese neighborhood came under heavy patrol. It was the afternoon of December 7, 1941, and Japanese planes had just bombed Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor . Police had blocked off the district so residents couldn’t leave the area. Other officers roamed the streets by foot, car, and horseback. Armed Coast Guardsmen took over the offices of the two daily Japanese newspapers.

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war with Japan and officially entered into World War II . Anti-Japanese sentiment and war hysteria reached peak levels. The FBI increased surveillance of Japantown, and agents raided the homes and businesses of local leaders in the Japanese community.

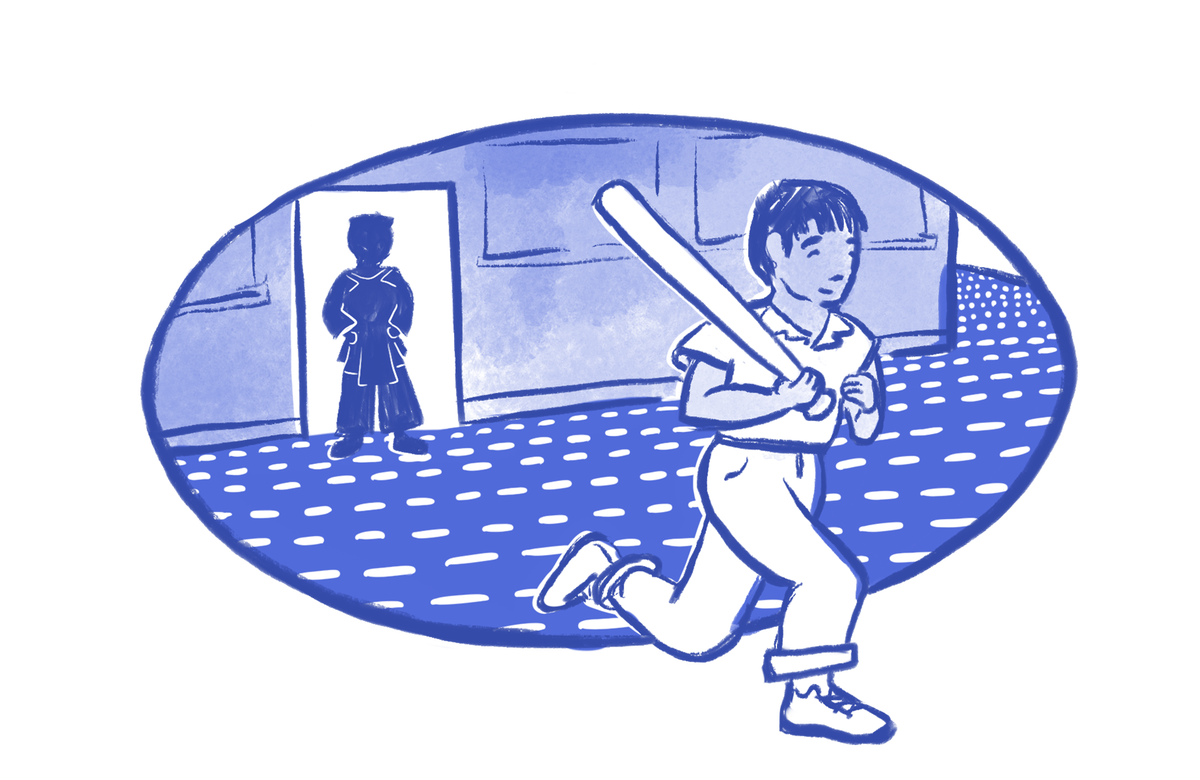

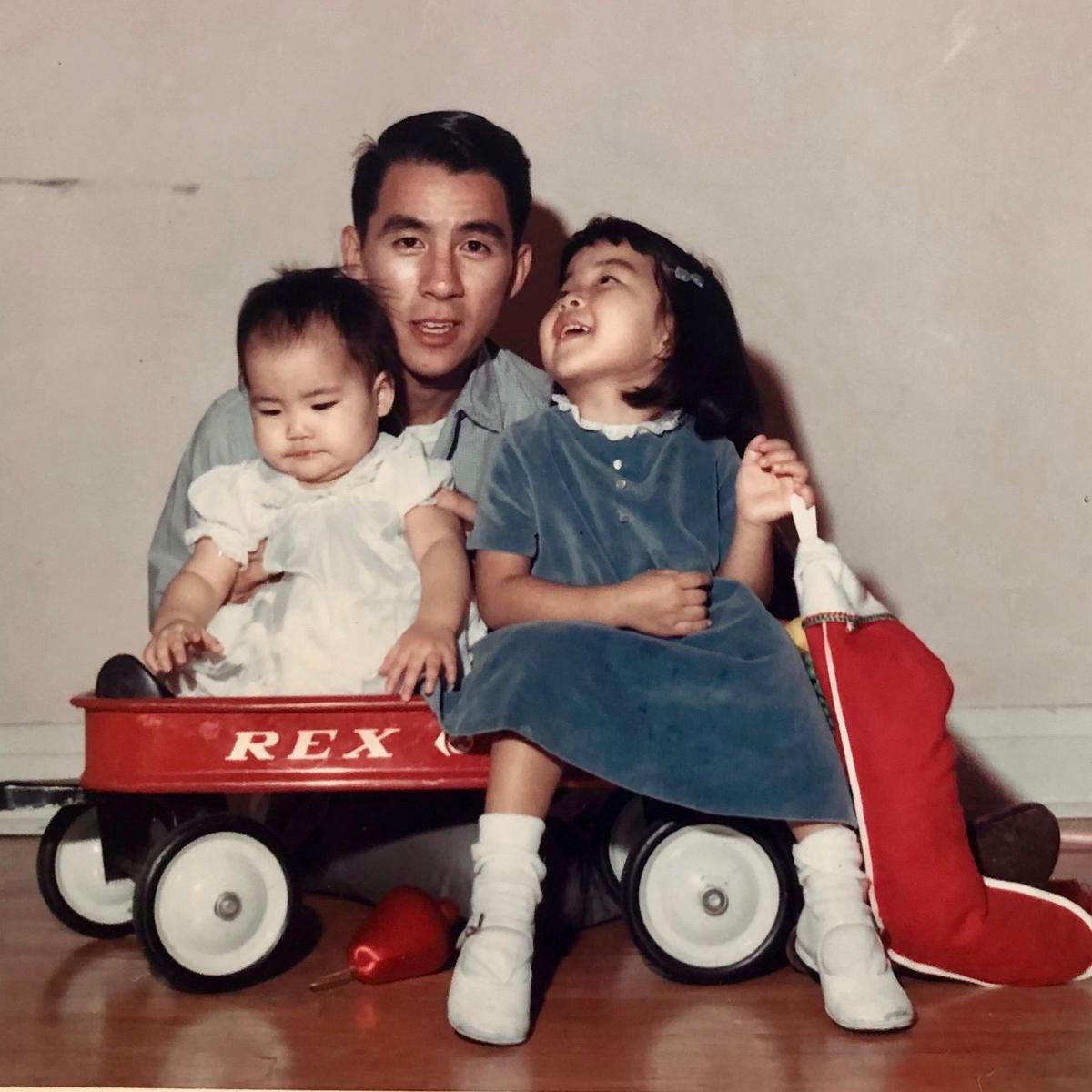

Kaz’s dad was one of those leaders. He worked as a bookkeeper at a Japanese bookstore by day, but taught the Japanese martial art of kendo during his free time. He’d grown up in a well-to-do family in Japan and was trained in many Japanese arts like calligraphy, Japanese flute, classical singing, and kabuki theater.

Because he taught a Japanese martial art, Kaz’s dad was included in the FBI’s Custodial Detention List . The list ranked Japanese business, cultural, and religious leaders based on their suspected “dangerousness” to national security. Those listed were candidates for arrest — regardless of whether there was any evidence of collusion with Japan.

In the months after Pearl Harbor, hundreds of Japanese community leaders were arrested by the FBI. Kaz’s family moved between San Francisco’s Japantown and the nearby city of San Mateo, and the changes in address made it difficult for the FBI to locate Kaz’s dad.

Eventually, on March 4, 1942, two agents knocked on the door of Kaz’s San Mateo apartment. They said that because Kaz’s dad taught kendo, they would need to do a thorough search of the place.

Why did the FBI arrest Kaz's dad?

During their search, they confiscated a Japanese flower arrangement Kaz’s mom was working on, calling it an incriminating piece of evidence.

Then, before Kaz could process what was happening, they took his dad.

After his dad’s arrest, Kaz’s mom was left alone to care for Kaz, a toddler, and his baby brother Shizuo, or “Shibo,” who was only a few months old. With the family separated, Kaz’s mom wanted to be closer to her family. So she brought Kaz and Shibo to live with her parents, who lived in the city of Lodi about two hours east of San Francisco.

They didn’t stay there for long. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had already issued Executive Order 9066 , dividing the West Coast into military zones and setting into motion the forced removal and imprisonment of around 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in those zones. In late spring, Kaz and his extended family were sent to a temporary “assembly center” in nearby Stockton, California. They lived there for several months while a newly created government agency called the War Relocation Authority (WRA) built what it called permanent “relocation centers.” The WRA’s term was a euphemism — these were in fact concentration camps designed to confine civilians for military and political purposes. Japanese Americans were never charged with any crimes nor given the right to a fair trial. They were imprisoned solely because of their Japanese ancestry.

By fall, the permanent concentration camps were ready. Kaz’s family was sent to one called the Rohwer in southeastern Arkansas. During the train ride, guards ordered Kaz and other passengers to keep the window curtains closed for the duration of the journey. They rode in darkness for days.

Rohwer was built on swampland, high in humidity and mosquitoes. Kaz and his extended family were divided into different barracks, and his uncles would often come over to babysit him and Shibo. But the question lingered at the back of Kaz’s head: Where’s Dad?

In March of 1943, Kaz’s mom received a life-changing letter from his dad. It had been more than a year since he was arrested by the FBI.

The good news: The government had given their family permission to reunite.

The bad news: If they wanted to reunite, the family would have to move into a Department of Justice detention camp.

Ask Kaz...

Chapter TwoCriminals with no crime

Kaz , 4

1943 | Crystal City, Texas

Kaz squatted and planted his fists on the hot Texas soil. He was in Crystal City Internment Center , and this was the last match of the camp sumo tournament. He’d been in the ring for several bouts already and beaten each opponent.

After the referee gave them the cue to start, Kaz’s opponent charged at him like a bull. Like a Spanish matador, Kaz stepped aside at the last second and watched as the kid blew past him and out of the ring. It was an easy win.

When Kaz brought home the tournament prizes that night, his mom gushed about how proud she was. Kaz’s dad didn’t say anything — he was usually pretty reserved — but Kaz could tell he was pleased. While the FBI had initially arrested Kaz’s dad for teaching martial arts, how could a father not be proud of a son taking after him?

After Kaz’s family reunited at Crystal City, Kaz’s dad didn’t share much about what he’d experienced over the past two years. All Kaz knew was that the FBI first detained his dad at San Francisco’s immigration facility and, after multiple transfers, sent him to Camp Lordsburg , a Prisoner of War camp in the arid deserts of New Mexico.

While camps like Rohwer in Arkansas were managed by the War Relocation Authority, Lordsburg was managed by the Department of Justice and only housed Issei men deemed “enemy aliens.” The camp was notorious for a labor strike organized by detainees protesting excessive manual labor demands. It was also known as the site of fatal shootings of two elderly detainees by a guard.

While at Lordsburg, Kaz’s dad was stabbed by a drunk guard who was upset with him for singing in Japanese. The guard initially aimed for his face, but Junzo quickly turned away so the knife hit him in the back.

Once Lordsburg detainees were allowed to transfer to Crystal City to reunite with family, Kaz’s dad jumped at the opportunity.

Once his family reunited at Crystal City, Kaz appreciated the predictability of life, especially after all of the displacement over the past two years. The camp conditions were objectively better than what he experienced at Rohwer. Instead of flimsy barracks, his family lived in cabin-like housing with running water. There were sports facilities and even a swimming pool. Kaz started attending elementary school during the mornings and spent afternoons playing softball and sumo wrestling.

But while life in camp felt normal at times, there were daily visual reminders that they were prisoners of war.

The camp had 10-foot high barbed wire around the exterior, guard towers, and armed police patrolling inside and outside camp. Kaz’s family had to participate in daily head counts of all detainees. All letters coming in and out of camp were censored. Instead of cash, detainees received “camp scrip,” or tokens, that they could use to buy goods at the camp stores. This was to prevent people from stockpiling cash and attempting to escape.

Where do you think the sense of guilt and shame Kaz felt came from?

Sometimes, life in Crystal City was plain bizarre. Every Saturday, Kaz watched as German detainees, who lived in another area of camp, marched around the camp perimeter with a flag bearing a giant swastika. One time, Kaz ran into a man with a mangled arm — he had just unsuccessfully tried to capture an armadillo that had roamed onto the camp grounds.

On September 2, 1945, more than two years after Kaz arrived at Crystal City, Japan formally surrendered to the Allies. World War II finally ended after six years of fighting.

Japan was defeated — Kaz should’ve been relieved by this news, but he couldn’t help feeling unsettled. After being imprisoned by his own country, how could he hold his head high when people saw his face as that of the former enemy?

Ask Kaz...

Chapter ThreeAll-American boy

Kaz , 8

1947 | Chicago, Illinois

Kaz laid pairs of chopsticks next to the plates and rice bowls on the long wooden dining table. Setting the table for dinner was one of his many chores at the boarding house. It was a little after 5 p.m., and the boarders would be returning from their factory jobs soon. They always came home eager for home-cooked Japanese food.

The boarding house was located in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood on the city’s South Side. Kaz’s parents had inherited it from his aunt and uncle, who started the operation after moving to Chicago from camp. Kaz’s family joined them in the Midwest after spending a year in Seabrook, New Jersey, where his dad worked in a vegetable canning factory.

Kaz’s family was part of a wave of 20,000 Japanese Americans that ended up in Chicago in the years during and after the war. They were part of the WRA’s resettlement program, , which aimed to redistribute Japanese Americans across the Midwest and East Coast. Chicago was chosen as one of the main destinations for resettlement because the city needed workers to fill the void created by the war effort, and because Chicagoans were seen as more tolerant towards Japanese Americans.

As part of the resettlement program, the WRA didn’t want the Japanese to congregate in ethnic enclaves like San Francisco’s Japantown — they wanted them to spread out and assimilate into white, middle class society. In their “leave clearance interviews,” they included questions that hammered those assimilation goals, such as:

- “Will you assist in the general resettlement program by staying away from large groups of Japanese?”

- “Will you avoid the use of the Japanese language except when necessary?”

- “Will you try to develop such American habits which will cause you to be accepted readily into American social groups?”

However, due to housing shortages and discrimination, Hyde Park was one of the only places in the city where Japanese people could secure housing in Chicago in the initial years after the war. As a result, Kaz's family's boarding house became the first stop for many single Japanese men resettling to Chicago.

While Kaz’s dad was busy working in a factory, his mom managed the boarding house. She cooked all the meals, cleaned all the rooms, and washed all of the bedsheets and towels manually. Kaz helped her by shoveling coal and sweeping and mopping the floors. While Kaz resented all of the chores involved in running the place, he enjoyed being around the boarders, who represented a wide range of ages and life experiences.

There was George, who coached him in boxing and showed him the proper footwork for someone who was left-handed. Then there was the mechanic who taught him all about cars. Another boarder had a xylophone and showed Kaz the basics of how to play.

More than anything, Kaz loved evenings at the boarding house when all the men retired to the parlor after dinner. There, they would smoke and play rounds of Hanafuda, a competitive Japanese card game. Kaz spent hours watching them play and would relay their strategies to his friends.

The boarding house was a place where Kaz could eat Japanese food, play Japanese games, and look Japanese without feeling self conscious. But outside of the safety of home, he couldn’t shake the shame he felt about being imprisoned during the war.

Kaz hated anything that made him stand out as Japanese. When he started 3rd grade, his teacher sent him to speech therapy because he was rolling his “r’s” and the other kids couldn’t understand him. Until moving to Chicago, Kaz mostly spoke Japanese with his family and had no idea he had an English speech impediment. After being put in speech therapy, Kaz pushed back every time his mom made him go to Japanese school. He didn’t put effort into the classes, and eventually stopped speaking the language.

How did Kaz try to prove he was an American? What does being “American” mean to you?

Then there was the embarrassment every time people couldn’t pronounce his Japanese name, “Kazuo.” During his sophomore year of high school, Kaz decided that he’d had enough and changed his name to “Gene.” His brother Shibo followed suit and changed his name to “Michael.”

Kaz did everything to prove he was as “American” as anyone else. Instead of practicing martial arts like his dad, who founded a kendo dojo in Chicago, Kaz embraced activities like Boy Scouts and sports like baseball, football, and basketball.

Eventually, Kaz started college to pursue a career in physical education, and became further separated from the Japanese community he grew up around. Once he took his first coaching job and moved to the suburbs, the majority of the colleagues he interacted with were white.

Soon, the Japanese community he grew up around in Hyde Park became a distant memory.

Ask Kaz...

Chapter Four“Be proud you’re Japanese.”

Karen , 18

1983 | Park Ridge, Illinois

Karen sat on the floor of the Park Ridge Public Library, defeated. After combing through the shelves for hours, she’d only found one chapter in one book that matched the topic she was looking for.

Karen was trying to write a high school paper about the Japanese American incarceration camps during World War II. She’d chosen to research the subject after reading a paragraph about them in her U.S. history textbook. But the three sentences dedicated to the topic barely scratched the surface, and Karen wanted to learn more.

What happened to Japanese Americans during World War II felt like a shameful secret in Karen’s family. Her parents referenced a place called “camp” once in a while, but never went into much detail. Karen’s mom Helen had tried to talk about the camps in the valedictorian speech she gave her senior year of high school, but her principal saw the draft and made her take everything out.

Karen could only write so much using the one library book she’d found, so she decided to interview her parents and grandparents about their experiences.

Her parents had both been toddlers during World War II, so most of their recollections were told from the perspective of kids who didn’t fully understand what was happening.

Her grandparents were reluctant to talk, and didn’t mention anything about their feelings towards being imprisoned. Rather, they focused solely on facts — like the changes in location over the years. Karen felt their matter-of-fact attitude embodied the Japanese phrase “Shikata ga nai,” which translates to: “It cannot be helped.”

After writing her school paper, Karen was angry that her family had been treated this way by their own country. It reinforced a belief she’d come to over and over growing up: No matter how hard her family tried to prove they were Americans, people looked at them and saw them as perpetual foreigners .

Karen couldn’t count how many times she’d also been bullied for being Japanese. Microaggressions were a normal part of life growing up Asian in the mostly-white suburb of Park Ridge. Kids would pull their eyes into slits, call her “chink,” a racist slur for someone of Chinese descent, and shout “Go back to your country!” Karen never understood that last phrase. She was born in the United States, so where exactly was she supposed to go back to?

Karen’s dad Kaz was also bullied by his own colleagues because of his Japanese heritage. Kaz was a gym coach and school counselor at Prosser Career Academy, a vocational high school on Chicago’s Northwest side. Sometimes on December 7th, the anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Kaz’s coworkers would decorate his office with airplanes and Japanese flags. They’d laugh and shout, “You did this because you’re Japanese!”

Kaz would come home and tell the family about the “hilarious” yearly tradition. But as much as her dad brushed it off, Karen resented that her dad was the butt of a joke. Did those colleagues even know about the Japanese American incarceration camps?

How are Kaz and Karen’s relationship with their Japanese American identities similar? How are they different?

In order to fit in at school, Karen spent most of her childhood and teen years pushing away her Japaneseness. She played sports like basketball, volleyball, track, and soccer. She worked hard to earn the “citizenship award” every year in elementary school.

Karen’s only tie to Japanese culture was through the classical Japanese dance troupe she participated in on the weekends during elementary school, and through the yearly festival and picnic hosted by the local Buddhist temple.

But that soon changed. During Karen’s sophomore year of college at the University of Illinois, she learned about a study abroad opportunity in Kobe, Japan. Neither of her parents or siblings had ever been to Japan before. Karen decided she wanted to go. To prepare, she took Japanese language classes for the first time in her life.

Once Karen arrived in Kobe, she took classes at Konan University about Japanese language, history, art, and culture. She learned about the art of kabuki theater, and saw her grandpa’s acting prowess in a new light. She traveled to cities like Tokyo and Kyoto with the other exchange students. Part way through her program, her paternal grandma visited her and took her to the city of Hiroshima and the island of Shikoku to visit the gravesites of their ancestors.

When Karen returned to Chicago, she had a newfound appreciation for the culture she had spent her entire childhood pushing away.

She decided she wanted to add another major on top of her degree in engineering: Asian Studies, with a focus on Japanese language and culture.

Ask Karen...

Chapter FiveDefying stereotypes

Ryan , 16

2013 | Highland Park, Illinois

Ryan’s face flushed with shame and rage. His t-shirt and shorts were soaked from standing outside in the rain. He stared at the car where his friends sat inside, warm and dry. He could hear their laughter amidst the music blasting from the radio.

Today Ryan had gone to a new friend’s house to play basketball. Being athletic helped him fit in with the white kids in his north Chicago suburb of Highland Park. Ryan’s grandpa Kaz was a P.E. teacher and had coached him in sports since he was a toddler.

Soon after the group started playing, it started to downpour. Everyone sprinted to the new friend’s car for shelter.

“I don’t want a ‘Chink’ in my car,” the new friend sneered.

The racial slur cut through Ryan like a knife. Paralyzed, he waited to see how the rest of the group would react. One by one, the others — many of them friends he’d known for years — laughed and followed the new friend into the car, leaving him out in the rain.

What happened during the basketball game was just one in a long line of incidents that singled Ryan out for being Asian. He realized he was different from others as early as kindergarten. He was on a playdate and came home crying to his mom after the other kid pulled his eyes at him. In middle school, his soccer teammates called him “Chino,” the Spanish word for “Chinese.” In high school, his friends made a group text chat titled “Squad plus Chinky.”

Ryan’s parents knew they couldn’t always protect him from bullying, so they tried to provide experiences that instilled in him a sense of pride in his Japanese and Taiwanese heritage. Even though they were Christian, his mom would take him to the annual Obon festival at her parents’ Buddhist temple. Every summer, Ryan’s dad took him and his siblings to a week-long camp in Indiana hosted by the Taiwanese American Foundation, or TAF, which he served on the board of. At camp, Ryan was surrounded by other Taiwanese kids. They participated in workshops led by Taiwanese community leaders and sampled Taiwanese noodle dishes and bubble tea at a camp event called the “Night Market.”

In Highland Park, Ryan stood out as the lone Asian — ridiculed for his appearance and reduced to a stereotype. But when he was in spaces like the TAF “Night Market,” he was a part of a community that celebrated its culture. The two worlds couldn’t have felt further apart.

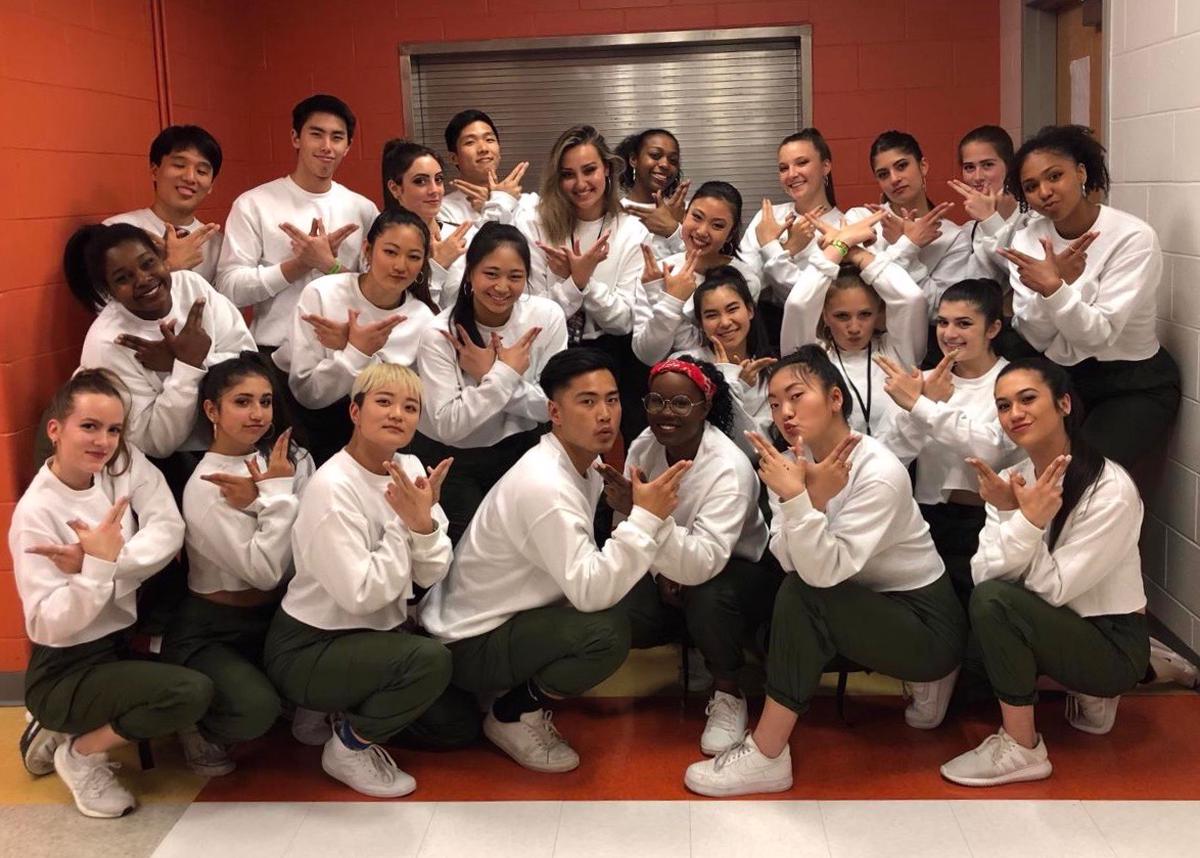

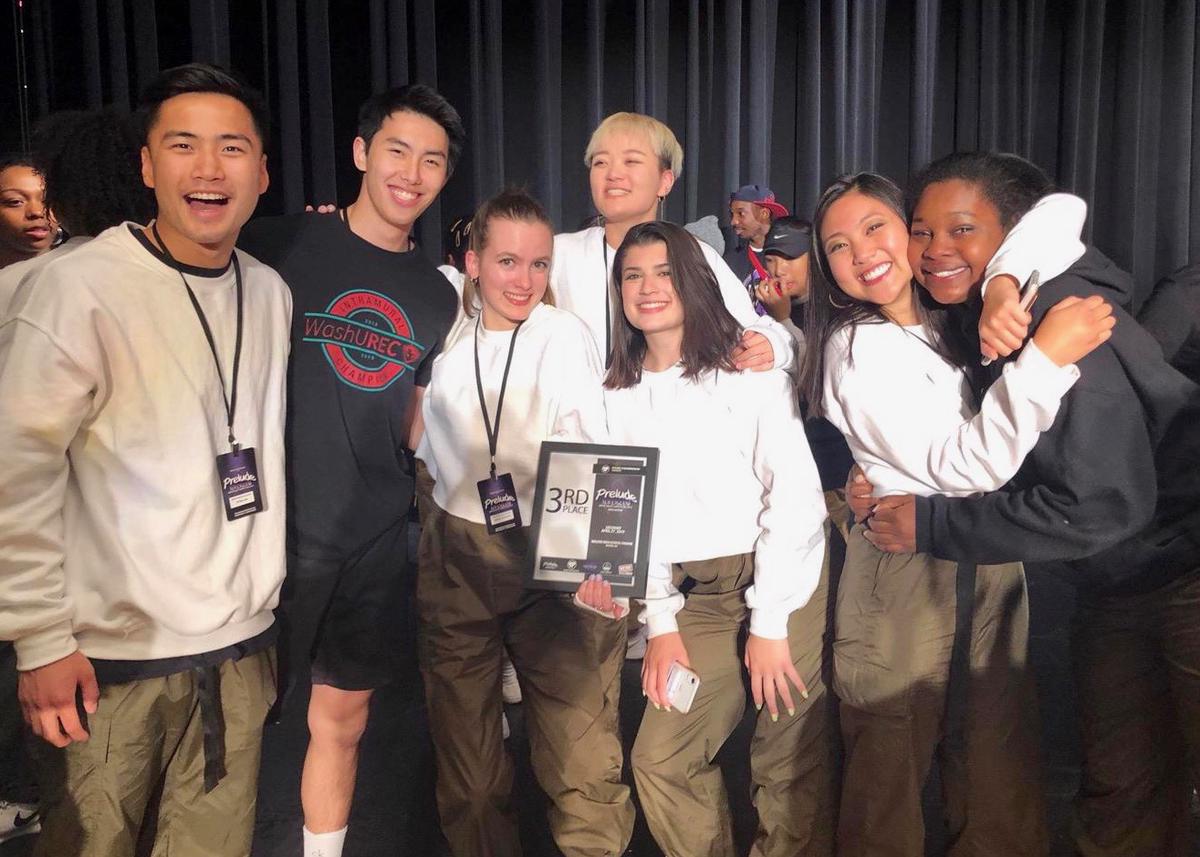

That all changed when Ryan went to college at Washington University in St. Louis. There, he joined a competitive hip hop dance team called WashU Hip Hop Union, or WUHHU. Through WUHHU, Ryan met Asian Americans who’d grown up all over the country. Many of them were from places like the West Coast where it was much more acceptable to be Asian. They were proud of their food and culture. They were proud to be Asian.

Ryan’s new friends were curious to learn about his family story, so he told them about how his Japanese American grandparents were incarcerated during World War II. They introduced him to different types of Asian cuisine like Korean barbecue and xiaolongbao, or Chinese soup dumplings. They invited him to campus events celebrating holidays like Lunar New Year.

Slowly, the shame Ryan had always associated with being Asian started to fade, and his self-confidence grew.

After graduating in the spring of 2020, Ryan decided to spend a year teaching Chicago high school students through a program called Americorps. He did it in part to follow in his grandpa Kaz’s footsteps. Coincidentally, the CPS school Ryan was assigned to is a ten minute drive from the school his grandpa worked at for decades.

Ryan’s students are mostly Black and Latinx. At the beginning of the school year, one of them asked him, “What race are you?” After Ryan responded, “Asian,” another student asked, “Do you like the movie Kung Fu Panda?”

Ryan realized that he was likely one of the only Asian people his students had met. All of his interactions with them would form their understanding of what other Asians were like. Ryan didn’t take this responsibility lightly — he knew from experience that Asian stereotypes like the Kung-fu master or the nerdy model minority are inaccurate and damaging. He wanted his students to know that Asians could be star athletes and confident hip hop dancers — parts of his identity that he was proud of.

How are stereotypes harmful? What can we learn from Ryan about how to combat them?

Ryan is also trying to give his students the acceptance he never had growing up. To get to know them better, he opens class by asking them what they did over the weekend. Sometimes students have talked about baking a tres leches cake, a type of Latin American sponge cake; other times they’ve shared stories about celebrating Kwanza. Ryan makes sure to ask lots of follow-up questions and always end by saying, “That’s super cool. Thanks for sharing.”

The words may seem casual and the gestures small, but Ryan knows that for young people, they can make a world of difference.