Chapter OneDreams for sale

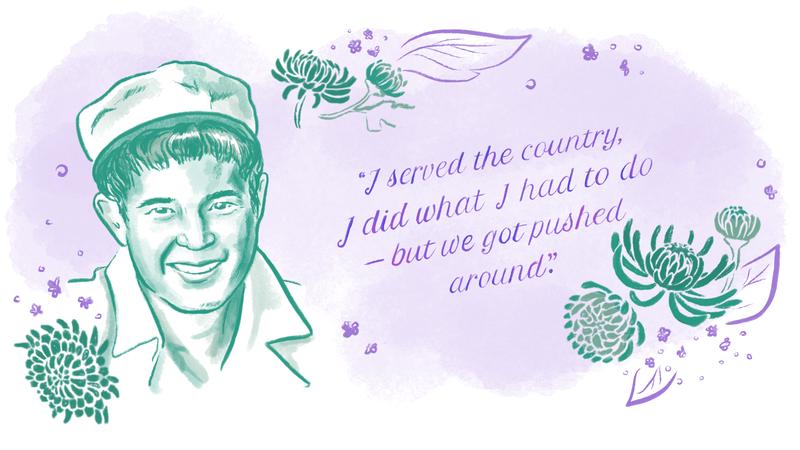

Min , 15

December 7, 1941 | Anaheim, CA

It was a warm late afternoon, and the sun was just starting to descend below the rows of broccoli that stretched out to the horizon. The sweet scent of orange blossoms drifted over from the neighbor’s groves. All of the hard work Min’s family had put in the past year was about to pay off with a big harvest.

Today was a day like any other, except for some unsettling news Min had heard from his parents: earlier that morning, Japanese planes attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and killed more than 2,300 Americans.

Japan's bombing of Pearl Harbor prompted the United States to officially enter World War II against the Axis powers of Japan, Germany, and Italy. While Min’s parents worried about what this meant for their family, Min was mostly focused on adjusting to his new high school. A few months earlier, the Imamuras had left a 10-acre plot of farmland they rented in Los Angeles and moved 30 miles southeast to Anaheim, a growing farming community in Orange County.

In Los Angeles, there had been lots of other Japanese American kids who attended Min's high school during the week and went to Japanese school and judo class with him on the weekends. In Anaheim, Min was one of the only Asian students — most of his classmates were Caucasian or Hispanic — and there was no Japanese school or judo academy nearby. He missed the tight knit Japanese American community he grew up around.

Min's family had left Los Angeles for the dream of owning land for the first time. In California, the Alien Land Act of 1913 prevented Min’s dad from owning or leasing farmland in the state because he wasn’t a U.S. citizen. This condition was essentially a way to bar all Asian immigrants from land ownership because, at the time, there was no pathway for them to become naturalized citizens. The U.S. government had limited naturalization to immigrants who were “free white” or of “African nativity and descent” in the Naturalization Acts of 1790 and 1870 . The Supreme Court upheld these restrictions in its 1920 ruling Ozawa v. United States .

While Min’s dad was an immigrant Issei , Min and his three older brothers were all second-generation Nisei — born in the United States and therefore citizens by birthright. This allowed the Imamuras to purchase land in Orange County in Min’s brother’s name. The new plot was more than twice the size of the previous one. Instead of growing a variety of berries and vegetables like they had done in Los Angeles, Min’s dad decided to focus on broccoli.

What motivated the Alien Land Law of 1913? Who benefited from it?

Despite his parents’ rising fears after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Min’s daily life stayed pretty much the same for the next couple of months.

He’d go to school and then walk home, marveling as the emerald broccoli fields ripened. In the late afternoon, he would complete the job he did every day: prepare the furo, or Japanese bath. It was an evening ritual everyone in the family looked forward to. Min was tasked with filling the deep redwood tub with fresh hot water. His dad got to soak first, followed by Min’s three older brothers, Min, and finally Min’s mom. Afterwards, everyone would gather in the kitchen to eat dinner as a family.

Soon, however, anti-Japanese sentiment reached a fever pitch. Wartime propaganda stoked fears that Japanese Americans living near military bases on the West Coast were engaging in espionage, sabotage, and surveillance. There were economic interests at play, too — white farmers who felt threatened by Japanese Americans’ success in agriculture fervently spoke about the disloyalty of Japanese Americans and lobbied for removing the entire community from the West Coast.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt answered these demands. On February 19, 1942, he issued Executive Order 9066 , which divided the West Coast into military exclusion zones and gave the military the authority to remove any people from those zones. This set into motion the forced removal and imprisonment of around 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, including Min and his family.

Initially, Executive Order 9066 divided the West Coast into two military zones. Orange County, where Min’s family lived, was part of Military Zone 1. Min’s parents heard that all Japanese people living in Zone 1 would be removed and imprisoned, so they quickly packed what they could fit into their truck and drove north to Sacramento, California, which was in Zone 2. Because everything was so rushed, they weren’t able to sell their land or any of their farming equipment.

By the time Min and his family had left, their broccoli harvest was ripe and ready to be picked.

Ask Min...

Chapter TwoThe last brother left at Amache

Min , 16

1942 | Granada, Colorado

Min exited the train and took his first breath of hot, dusty Colorado air. It took some time for his eyes to adjust to the bright sunlight after spending the past 24 hours in almost complete darkness.

The overnight train ride had been sweaty and uncomfortable. The soldiers onboard made sure that the window curtains were pulled down the entire way, so nobody had any idea where they were at any given point. The train had no sleeper cars, so everyone had to sit upright through the night. Min felt especially bad for all the old people, and for the mothers with babies.

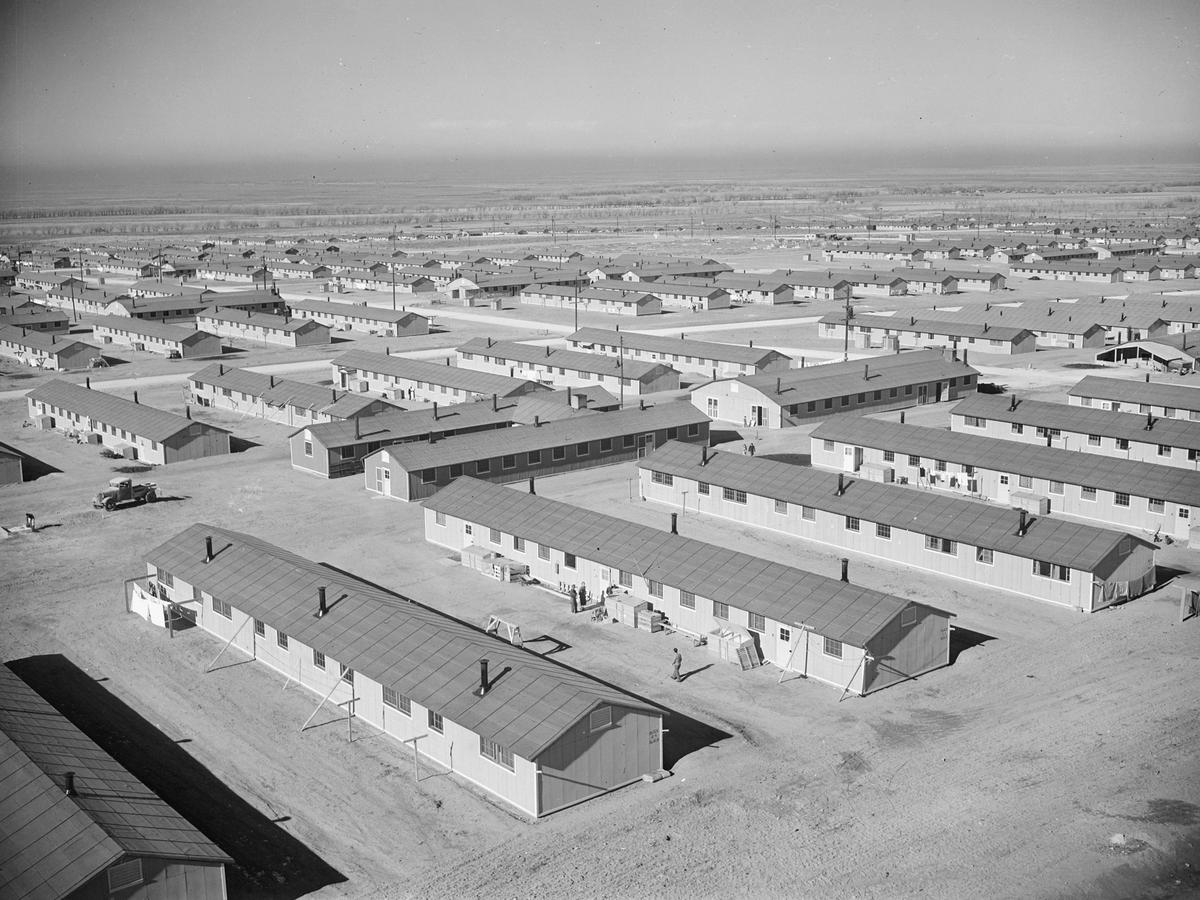

A few months earlier, Min’s parents had hoped to spare the family from being imprisoned by fleeing to Sacramento, which was in Military Zone 2. But not long after they moved, the government changed its mind and decided to forcibly remove all Japanese Americans in Military Zone 2 as well. Min and his family spent the next three months detained at a makeshift “assembly center” in Merced, California as they waited for the construction of a permanent “relocation center.”

Both of these government terms were euphemisms — these centers were in fact concentration camps designed to confine civilians for military and political purposes. Japanese Americans were never charged with any crimes nor given the right to a fair trial. They were imprisoned solely because of their Japanese ancestry.

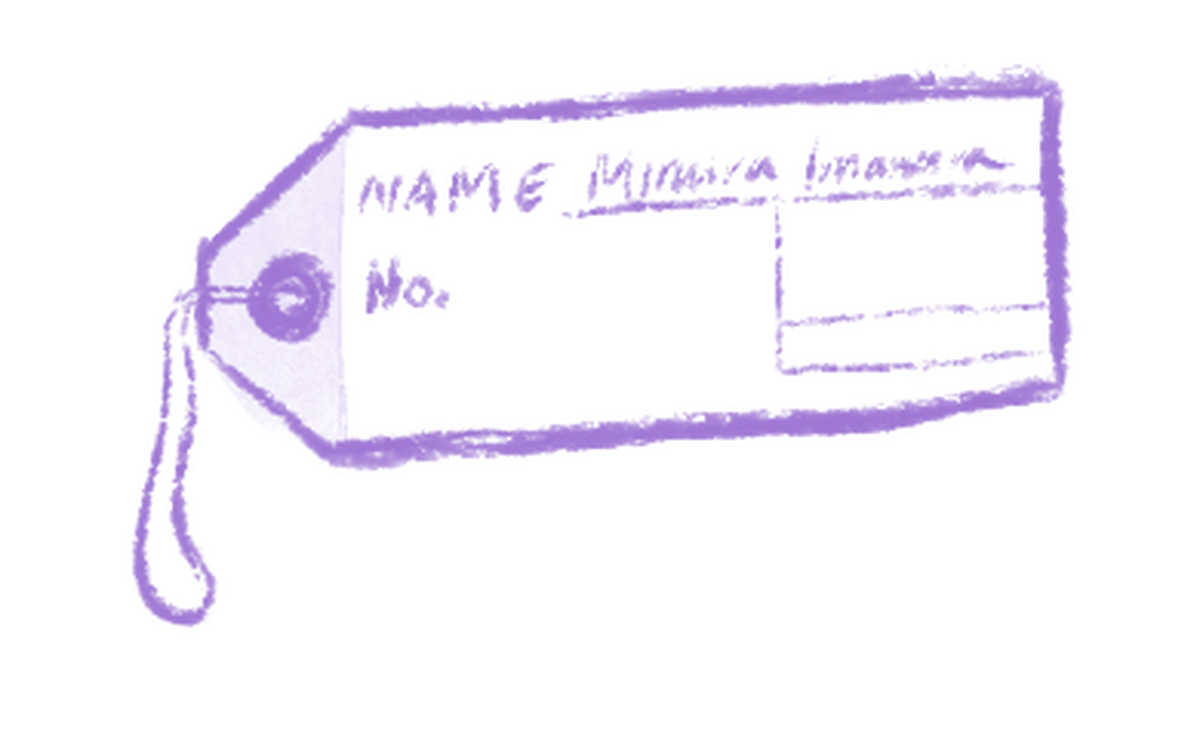

Once the permanent concentration camps were ready, military personnel gave Min and his family numbered ID tags to wear and ordered them to board a train, bringing only what they could carry. After a more than 1,000-mile journey, they finally arrived at the train station in Granada, Colorado. Min and his family loaded their suitcases onto a smaller truck and took a short ride to their new home, which they would refer to as “Camp Amache.”

As they drove up over a hill, the camp came into full view: an expanse of wooden barracks with guard towers and barbed wire fences surrounding them. Beyond that, the land was flat and barren save for some sage brush.

It didn’t take long after arriving before Min’s family found themselves busy with the daily chores and routines of camp life. Min’s dad got a job cleaning the laundry rooms and bathrooms. Min and the other kids attended classes at the camp school, which offered similar classes to his school back in Anaheim but with limited textbooks and no library. After school and on weekends, Min would often play baseball or participate in Boy Scout troop workshops organized by camp elders.

How did Min’s family structure change in camp?

In fact, Min became so busy with his new friends that he hardly spent any time with his family except for sleeping in the barrack together at night. His family even stopped eating meals together like they used to back in California.

Over the next year, Min’s family split up even further. Min’s three older brothers obtained leave clearance from camp to pursue work in cities outside of the military zones on the West Coast. One took a job with a seed company in Walla Walla Washington, another went to Denver, Colorado to bake pastries at a country club, and the third brother got a job in a welding facility in Iowa.

By the time he started his senior year of high school, Min was the last brother left at Amache.

Ask Min...

Chapter ThreeThe “Loyalty Questionnaire”

Min , 17

1943 | Granada, Colorado

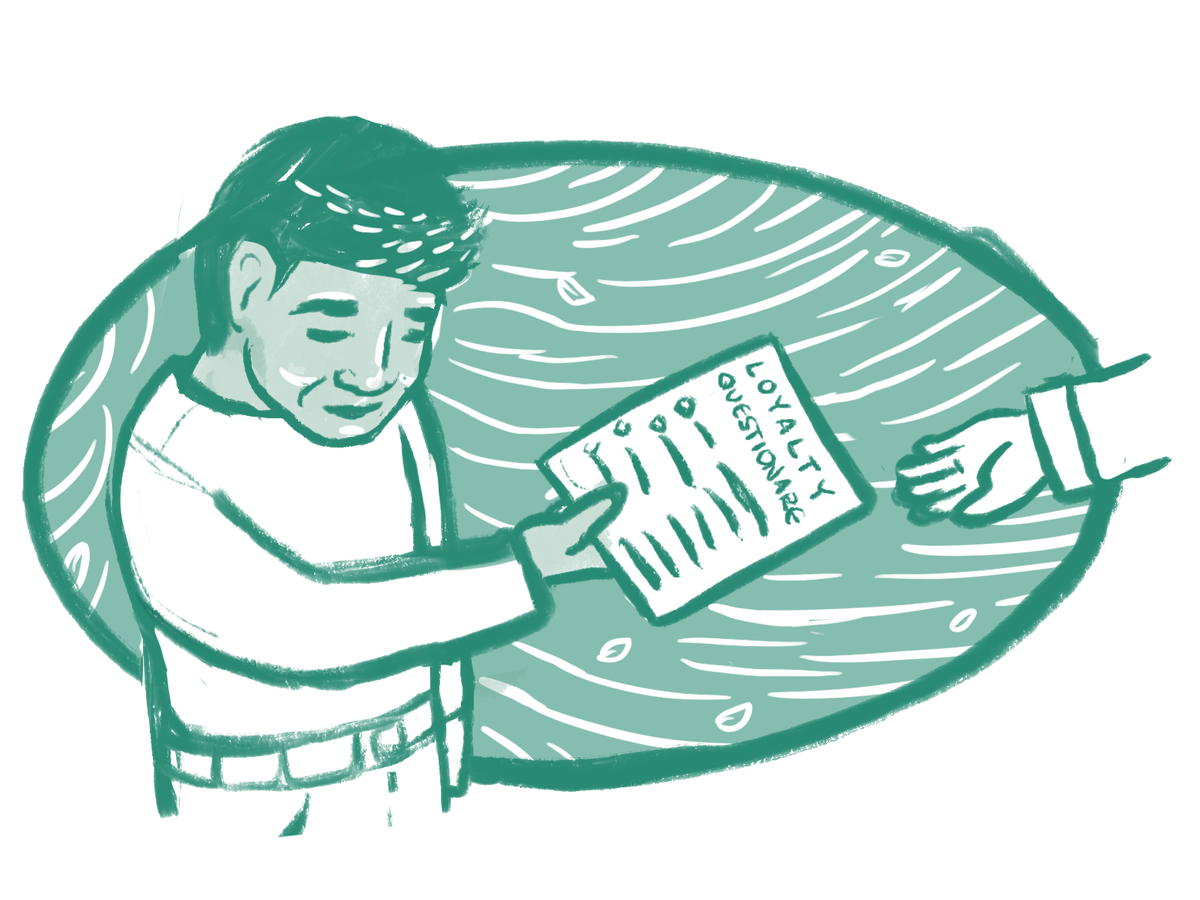

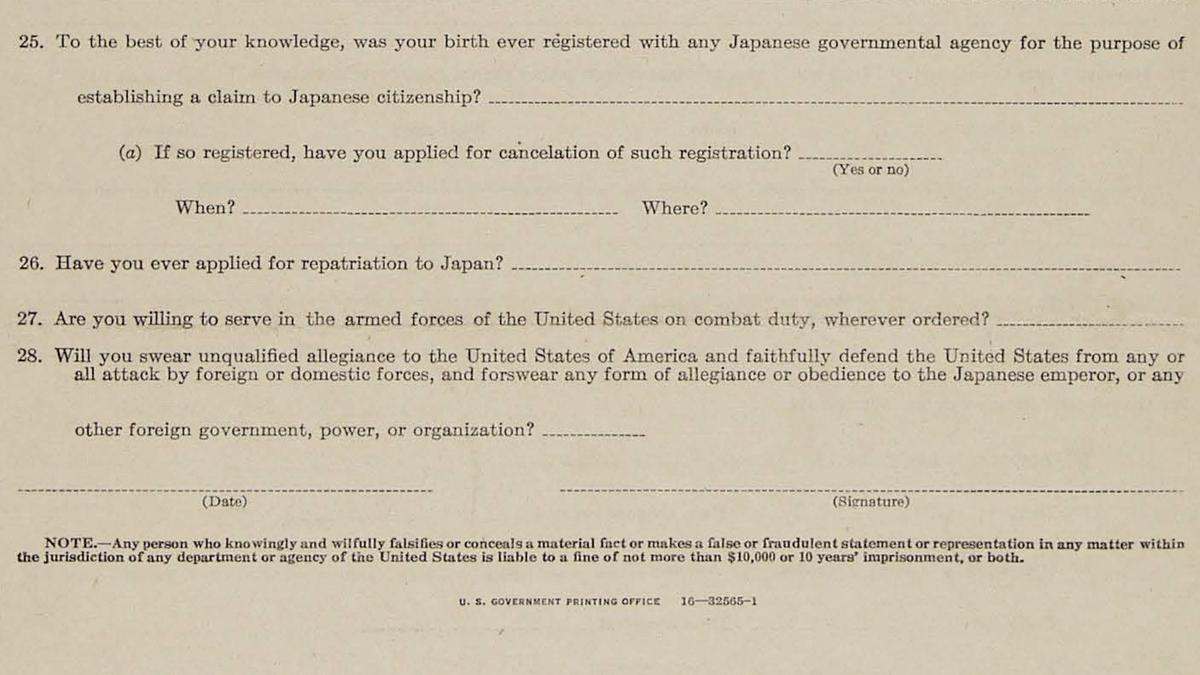

Min’s hand hovered over the page in front of him, and he stared at the final two questions he had left to answer. He was completing the so-called “Loyalty Questionnaire” required of every incarcerated Japanese American who was at least 17 years old. Min had heard that the last two questions in particular were causing controversy — and even violence — within some camp communities. They read:

Why did Min answer “Yes, Yes” to the Loyalty Questionnaire? How would you have answered it?

27. Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

Some of Min’s friends worried that responding “yes” to Question 27 would mean they were volunteering for combat. They thought it was unfair they were being asked to risk their lives for a country that imprisoned them and their families.

As for Question 28, it seemed odd to Min, an American-born Nisei , to renounce his allegiance to the Emperor of Japan when he had never even been to Japan nor felt any loyalty to the Emperor. But he knew that this question would trouble his parents’ generation, the immigrant Issei , who the U.S. excluded from ever becoming citizens no matter how long they lived in the country. Renouncing loyalty to the Emperor of Japan and swearing allegiance to a country that did not accept them as citizens seemed like a dangerous gray area to be in.

Before he could change his mind, Min took a deep breath and wrote “yes” and “yes” next to both questions.

A year later, Min received a notice that he had been drafted into the U.S. army. He had just turned 18 and still hadn’t finished high school, so he petitioned — with success — to be allowed to graduate before entering the army. He eventually enlisted the following year and was sent to Camp Blanding, a military training base in northeastern Florida. There, he trained with other Japanese American men as replacements for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) , a segregated, all-Japanese American unit that had spent the past two years fighting in Europe.

After several months of training, Min and several hundred other Japanese American soldiers were sent to Europe. When they arrived, half of the group was sent to Italy as replacements for the 442nd RCT. The other half, which included Min, was sent to Germany with the 390th Military Police Battalion.

Min was in Germany on September 2, 1945, the day Japan formally surrendered to the Allies, ending World War II after six years of fighting. He felt lucky that he hadn’t been sent into combat like many of his fellow Japanese Americans who served in the 442nd RCT. Those troops had fought in some of the bloodiest battles, including the heroic rescue of the Lost Battalion and the breaking of the Gothic Line in Italy. In total, the all-Japanese American troops suffered casualties that totaled 800 killed or missing in action.

Instead, Min served as a guard on freight trains traveling between Allied-occupation zones in Germany. From his view in the caboose, he saw firsthand the way the war had ravaged Europe.

In the summer of 1946, Min returned to the United States on a troopship called the SS George Washington. He breathed a sigh of relief when the Statue of Liberty came into view. He was finally home — although it was unclear where “home” even was anymore. During his two years in the army, Min hadn’t received one letter from his parents. He wondered about what happened to the broccoli farm in California, and whether his family would ever live together in the same place again.

Ask Min...

Chapter FourDigging up the past”

Gayle, Min's daughter

Chicago, IL

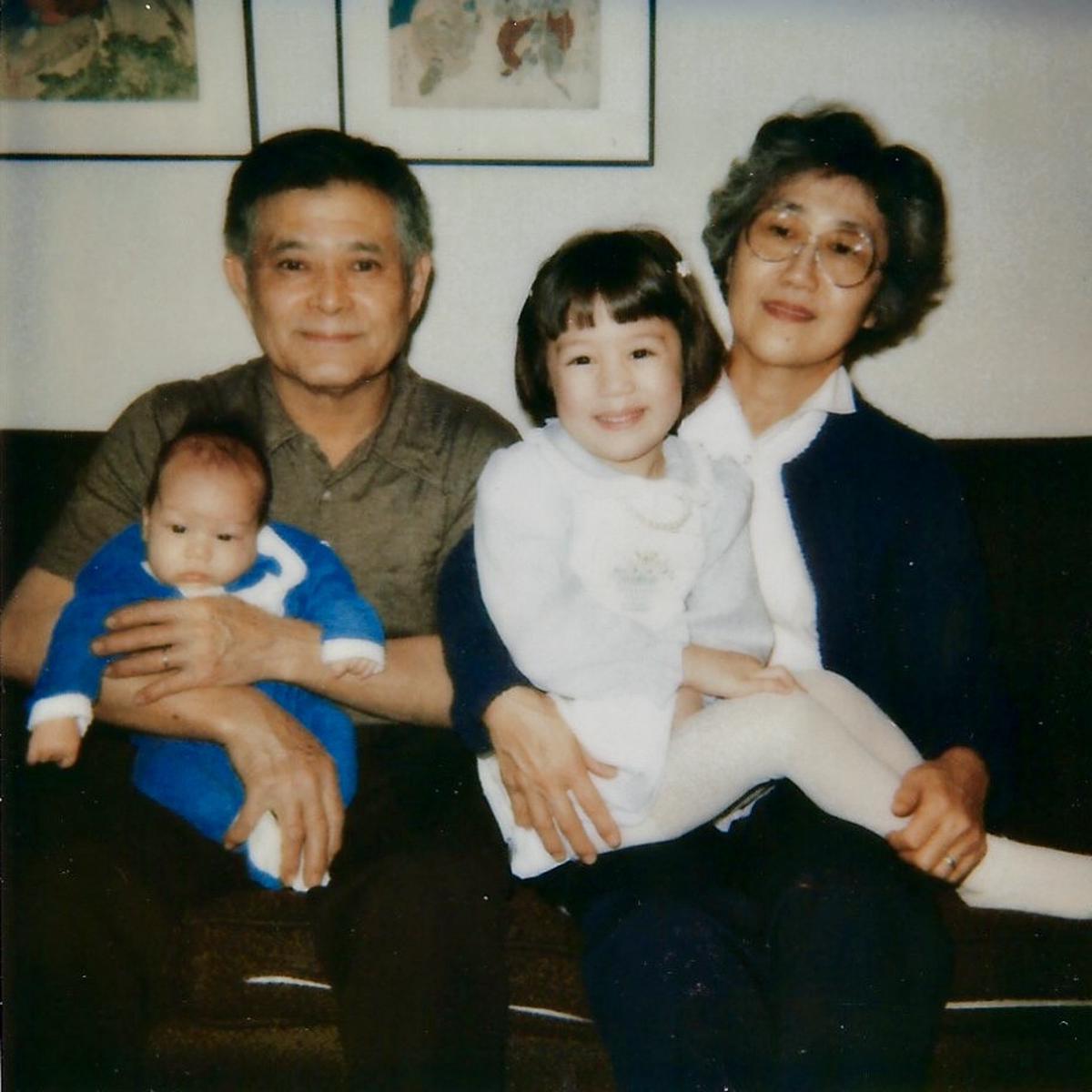

As a kid, Gayle often heard her parents talk about a place called “camp.” Whenever her dad met another Japanese American in Chicago, he’d first ask, “Where were you born?” followed by, “Which camp were you at?”

To Gayle, the exchange seemed like nothing more than a social icebreaker. She was aware that her parents had spent several years in a camp for Japanese Americans during World War II, and that her dad also served in the U.S. Army. But because her parents didn’t talk about these experiences with bitterness or anger, she didn’t dwell much on them.

Gayle was born and raised in Chicago. Her parents had moved to the city as part of a wave of around 20,000 Japanese Americans who came in the 1940s from the concentration camps. Most were part of a government resettlement program to redistribute Japanese Americans across the country and assimilate them into white, middle-class society.

Gayle’s mom Mary and her parents resettled to Chicago around 1944 and initially lived in the South Side neighborhood of Hyde Park. Hyde Park was one of the few areas Japanese Americans were able to rent apartments at the time due to housing discrimination. Gayle’s dad Min moved to Chicago a couple of years later after spending time with his older brothers who lived in Denver and Northern California.

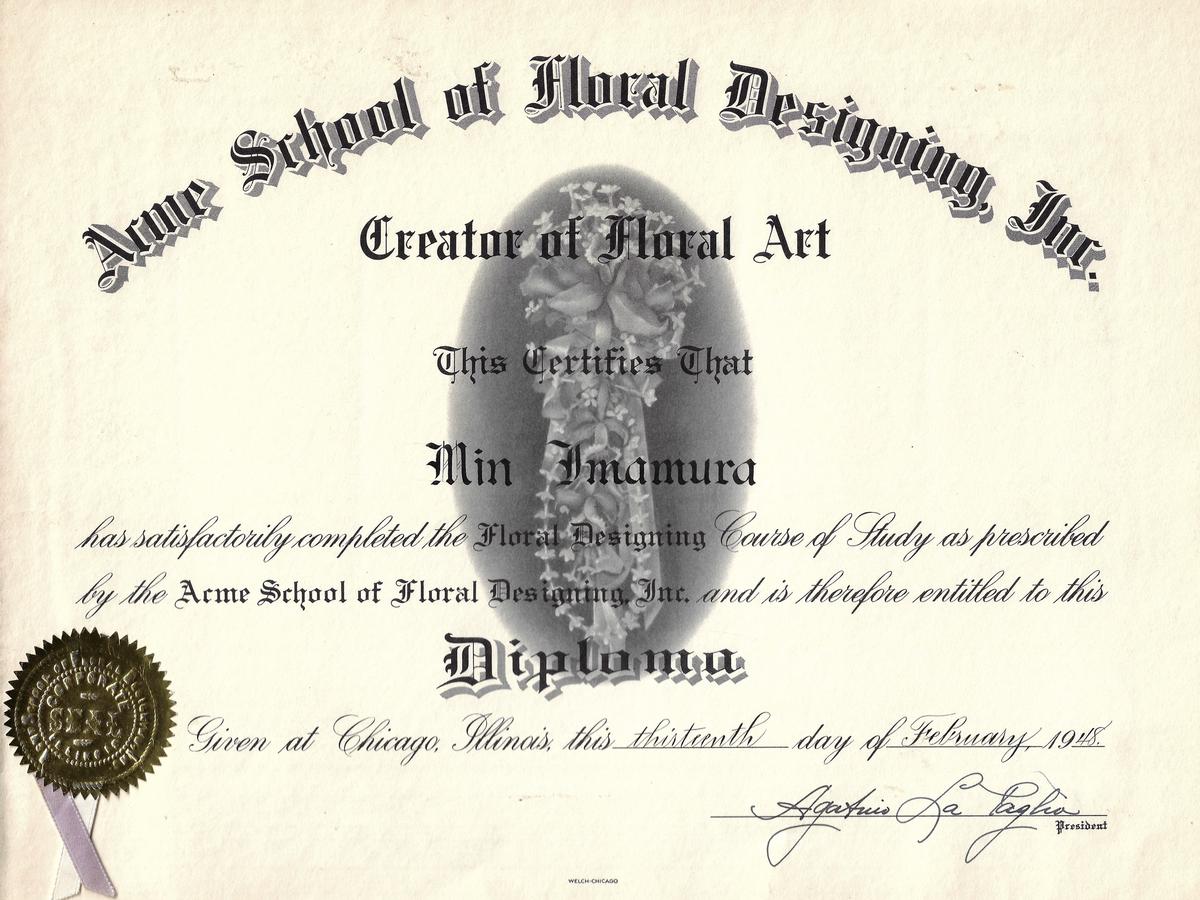

In Chicago, Min and Mary had to start life over from scratch. Mary got a job as a stenographer and was grateful to have a source of income to support her family. However, she was disappointed that she was never able to complete her college degree because she was forced to leave for camp when she was 17. Because Min was a World War II veteran, he was able to take advantage of the GI Bill to get a degree in floral design. He eventually got a job at a Jewish-owned flower shop on the city’s North Side, creating arrangements for lavish weddings held in the northern suburbs.

Min and Mary got married in 1950 and moved from the South Side to the North Side of Chicago, a pattern that many Japanese American families followed in the ’50s and ’60s. They bought a three-flat building in the Edgewater neighborhood and would live there for nearly 50 years.

Growing up, Gayle remembers her parents encouraging her to work hard and dream big. Her dad emphasized the importance of education and made an effort to attend every school assembly and graduation for Gayle and her three siblings. He would often tell them, “America is the land of opportunity. There isn’t anything you can’t do. Become whatever you want to become.”

For Gayle, that meant becoming a professional artist. In high school, she won a city-wide art competition and had an AP Art teacher who believed she had a promising art career. During her senior year, Gayle received a full ride scholarship to study studio art at the Art Institute of Chicago.

As she developed her art career, Gayle’s dad was her biggest supporter and cheerleader. While she was a student at the Art Institute, he’d build all of the 10-by-6 foot wooden stretchers she needed to mount her canvases. He came to all of her art exhibitions. When they both had free time, they visited almost every major art museum in the U.S. together.

In many ways, Gayle’s dad lived vicariously through her creative endeavors. He was an artist at heart, and Gayle felt that he would’ve made an incredible sculptor if given the opportunity. But because her parents had lost everything during the war, there was a glass ceiling on their education and career options. They invested everything in their kids in the hopes that the next generation would achieve success in ways they couldn’t.

Why do you think Gayle’s parents didn’t talk in detail about their incarceration experiences?

Some people might’ve responded to these limitations with bitterness and resentment. While Gayle’s parents knew what had happened to them during the war was wrong, they didn’t want their daughter to grow up with a chip on her shoulder. Their acceptance of hardship and injustice embodied the Japanese phrase shikata ga nai, which means, “it cannot be helped.” To them, it was easier to bury the past and move on with their lives.

It wasn’t until later in life that Gayle began to fully understand what her parents endured during the war. Her dad first started talking more openly about it when his grandchildren interviewed him about his experience at Amache for their school projects. Then he began reading books about World War II and attending Japanese American history events. Soon, Gayle and her dad formed a shared hobby of learning as much about Japanese American incarceration as they could.

In spring of 2018, Gayle’s dad was interviewed for “The Go For Broke Spirit,” a book about Japanese American men who served during World War II. After the interview, the author mentioned to Gayle that there was an upcoming pilgrimage to the site of Camp Amache in Granada, Colorado. Former incarcerees and their families were gathering to remember what they’d gone through and honor the Japanese American soldiers who fought and died during the war.

Gayle talked with her dad and he agreed to attend the pilgrimage. It had been more than 70 years since he’d last stepped foot on Amache, and he felt it would be meaningful to revisit that part of his life — especially with his kids and grandkids. So, in late May of 2018, Gayle and her dad made the 15 hour drive from Chicago to Colorado. Packed in the car with them were Gayle’s husband Cary, daughter Kara, and son-in-law Jonathan.

What Gayle saw and learned upon arriving at Amache would forever change her understanding of “camp.”

Ask Gayle...

Chapter FivePassing on history and heritage”

Kara, Min's granddaughter

May 2018 | Granada, Colorado

Kara squinted at the desert landscape in front of her and felt the dry, warm heat on her skin. It was only mid-May — she couldn’t imagine how hot it could get here during the summer.

Ahead of her, Grandpa Min trekked through the brush. He had so many stories about being a teenager in this place, which was the site of the Amache concentration camp he’d spent several years at during World War II. He pointed out the train depot where his family was dropped off after riding for a full day in complete darkness. He told her about the guard towers that used to surveille the premises. When they walked into a recreated barrack, he remarked that it was “too nice” compared to the conditions he remembered. His barrack didn’t have a brick flooring, only dirt. Instead of tight, uniform planks, the planks in his barrack had large cracks in between them that let in dust and heat.

During their pilgrimage to Amache, Kara’s family visited the camp museum and the former site of the barrack her grandpa Min lived in. Over the course of the day they befriended a local archeologist named Bonnie Clark, who explained how camp survivors, historians, and archeologists were literally piecing together the incarceration history. Dr. Clark said that Amache had been razed after World War II, but some researchers went to the local garbage dump to retrieve old materials. They’d found everything from hair pins to broken plateware to an urn for pounding mochi, a Japanese rice cake. The artifacts they uncovered revealed new details about camp life. One that stood out to Kara was how incarcerees had gathered rocks to construct a traditional Japanese garden and fish pond within the camp.

Kara imagined her grandpa as a teenager living behind barbed wire in this hot and barren desert. He’d been a cheerful and supportive presence throughout her life, always smiling and cracking jokes. As a kid, Kara would go over to his house for lunch and card games after her weekly piano lessons. He attended her high school track meets, met her prom dates, and even did the floral arrangements at her wedding. She knew he had been incarcerated during World War II, but being physically at Amache made her feel much more connected to that dark chapter in his life.

How did visiting Amache deepen Kara’s understanding of her grandpa’s incarceration experience?

Grandpa Min returned to Amache two more times over the next year — the second time was for a weekend called “Amache Community Open House,” which included an extensive archeological tour of the site. The third time was for a special visit with Dr. Clark to look through more artifacts excavated at Amache. During Min’s visits, he met other Japanese Americans who were also processing their wartime experiences. Sharing stories helped jog Min’s memory and give him a fuller picture of what the community had gone through.

After the family pilgrimage to Amache, Kara realized the importance of documenting and remembering the past. She saw how meaningful it was for her grandpa to learn about the artifacts that Dr. Clark uncovered, and to be in community with other Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated. The pilgrimage also gave her the opportunity to know her family history and be able to one day share it with her kids and grandkids.

The last big event Kara attended with her grandpa was the 2019 launch event for the “Go For Broke Spirit,” a book he was featured in alongside other Japanese American veterans. The event was held in a gallery space in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. Kara sat with her grandpa as he chatted with attendees and signed copies of the book. He seemed bewildered by all the attention he was getting for their service. “I’m such a simple man,” he remarked. “All I did was my duty.”

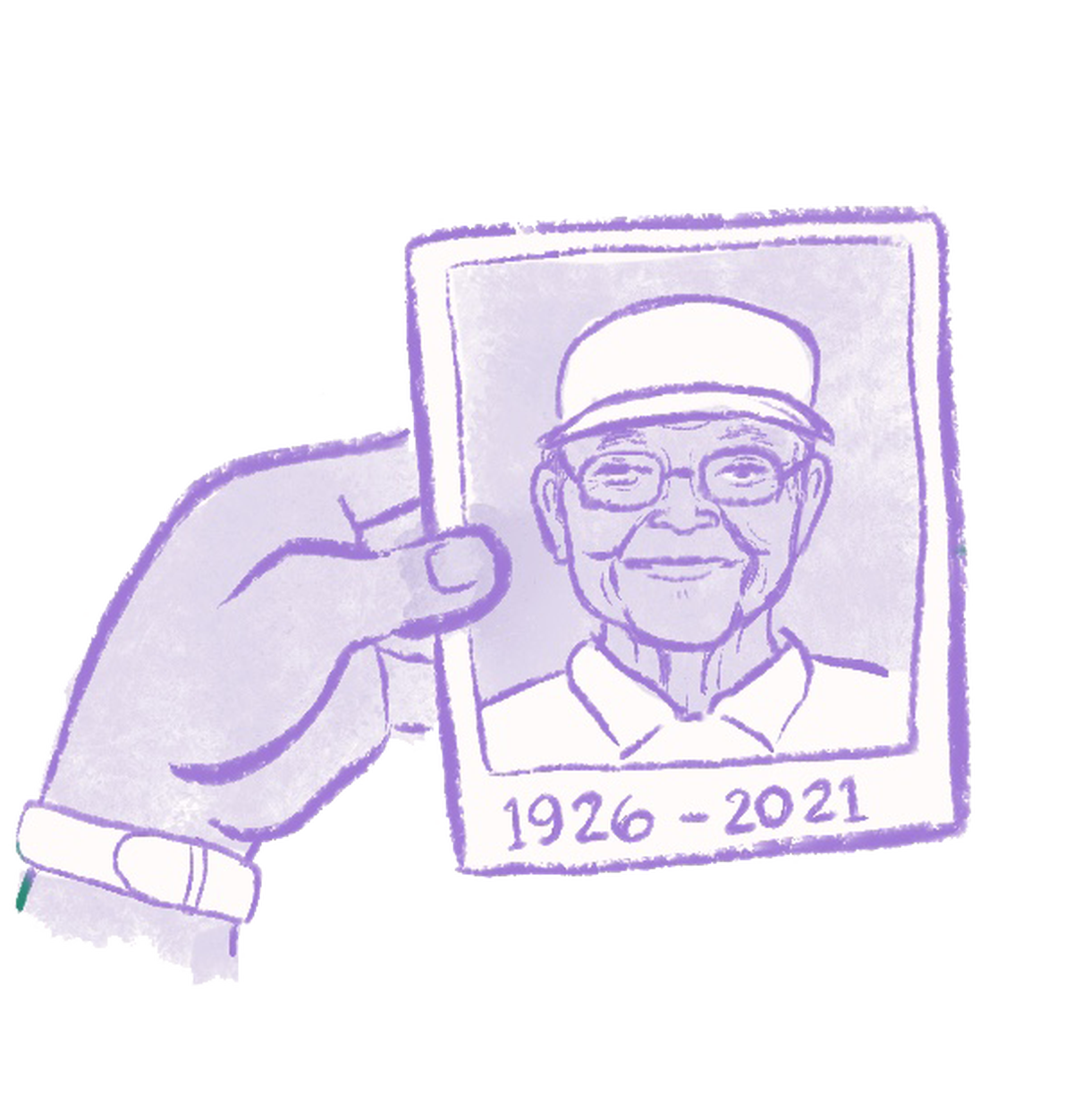

In early 2021, Grandpa Min passed away at the age of 95. These days, Kara is thinking a lot about how to pass down her grandpa’s story to her own daughter Ellie, who’s just a toddler. Kara wants Ellie to know how her great-grandpa and 120,000 other Japanese Americans were forced from their homes and incarcerated solely based on their ancestry. She also wants Ellie to know about the sacrifices Japanese American soldiers made to try and prove they were loyal Americans.

In February of 2022, the U.S. Senate voted unanimously to pass the Amache National Historic Site Act, which would establish Amache as part of the National Park System. This would move ownership and management of the site from a group of volunteers to the National Park Service. A National Historic Site designation also makes Amache eligible for additional federal preservation funds.

For Kara, this bill ensures that she and her family will have a physical place to return to when they want to reflect and remember their history. While her grandpa Min is no longer around, Amache will still be there for Ellie when she’s old enough to take her own pilgrimage.

When that time comes, Kara and her mom Gayle will be ready. They’ll tell Ellie about the hot and stuffy train ride to Colorado, the dusty baseball games, and the paper-thin barracks. They’ll explain why the last two questions on the “Loyalty Questionnaire” were so loaded, and what great-grandpa Min saw while riding in the caboose of a train across war-torn Europe.

By making this pilgrimage, Ellie will join the generations of her family before her in remembering the resiliency of her great-grandfather Min. While most people might only see a patch of dirt and rocks, Kara and Gayle will help Ellie to see a fish pond.